As the federal elections in Germany approach, we’re excited to share a series of three blog posts on topics related to the election. All three posts are written by students from one of Eva Wegner’s courses. This post is the second in the series.

Authors: Emine Mulgrew and Phillip Dornheck

On the 23rd of February 2025, the German Federal Election will take place. Politicians are taking every opportunity to convince voters that they are the best representatives of their interests. According to polling data, right wing parties are set to attain a majority vote from social groups that traditionally align their support with other parties1. This has the potential to lead to Germany experiencing the biggest swing towards the right since 19352. What is particularly striking is the engineering of right-wing parties to move their messaging to specifically target the “little man” or ordinary working people3. Right wing political parties such as the Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) and the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) have strategically framed themselves as representatives of the working and middle class, even when their policies largely benefit wealthier citizens. Similarly, in the UK this strategy was even more prominent amidst the 2024 election campaign. With politicians within the Conservative Party and Labour Party publicising their backgrounds and class status to present themselves as the more responsible party, capable of running the country4. This shift is significant not only in shaping election outcomes but also in reinforcing political inequality. Right-wing parties use class-based rhetoric to attract working-class support while implementing policies that disproportionately benefit the wealthy, leading to deeper political disparities.

A persistent question for those considering who to lend their vote to is; who will best represent my interests? The German solution to quantifying this has been the development of digital programmes such as Wahl-Swiper and Wahl-O-Mat. These programmes register your positions on issues ranging from migration regulation to sources of oil or power production. They then proceed to compare your answers to those submitted by the candidates. This produces a handy percentage response, clearly visualising the percentage of agreement between your own position and the political party. Due to the popularity of this tool, others have copied similar frameworks attempting to combat voter apathy and low turnout through simplifying accessing resources for those attempting to figure out how their personal ideology aligns with political party politics5.

This paints a nice picture of engaged voters, able to spend time and utilising tools to figure out the complex messaging of political parties. However, this is often a false reality. There are systemic barriers that prevent these tools from fully addressing political inequality. The time and resources that citizens can devote to political research differs depending on their lifestyle. Someone working multiple jobs, with caring responsibilities or who has not been exposed to political information before may find it disproportionately more difficult to engage with political resources6. This can create an increasingly difficult system to navigate when deciding who is the best candidate to represent your interests. Often this can result in voters deciding to support whoever is shouting the loudest. You may consider yourself an ordinary middle class German citizen, someone who has felt the economic squeeze of the economy stagnating and feels they have been ignored by mainstream political parties. If you hear certain political parties adequately acknowledging your hardships and promising to act in your best interest, then it is no surprise that you may feel more closely aligned with that party.

Political inequality does not merely influence electoral outcomes; it also affects policymaking, deepens economic disparities, and reduces trust in democratic institutions. As right-wing parties appeal to working-class voters while enacting policies that primarily benefit elites, this contradiction raises fundamental concerns about the future of political representation in Germany.

The Strategy of Claiming Representation

How Political Parties Shape Their Messaging

Political parties have utilised the complexity of the political system to expand their rhetoric and false claims of class representation to broaden their voter base, particularly among the working and middle class. This “little man” strategy, implemented by parties such as the AfD and CDU, has been an effective mechanism for increasing support in social groups where they previously lacked influence7. Promoting themselves as part of a social group or the only political party who could adequately represent the interests of the middle class8.

For voters trying to determine which party truly represents them, aggressive political marketing and contradictory claims by politicians make the decision challenging. Party leaders often claim that their policies benefit broad socio-economic groups, but post-election decisions frequently contradict these promises. For example, both the CDU and AfD promote policies that protect asset-rich individuals while reducing social welfare benefits, despite claiming to support the working and middle class9.

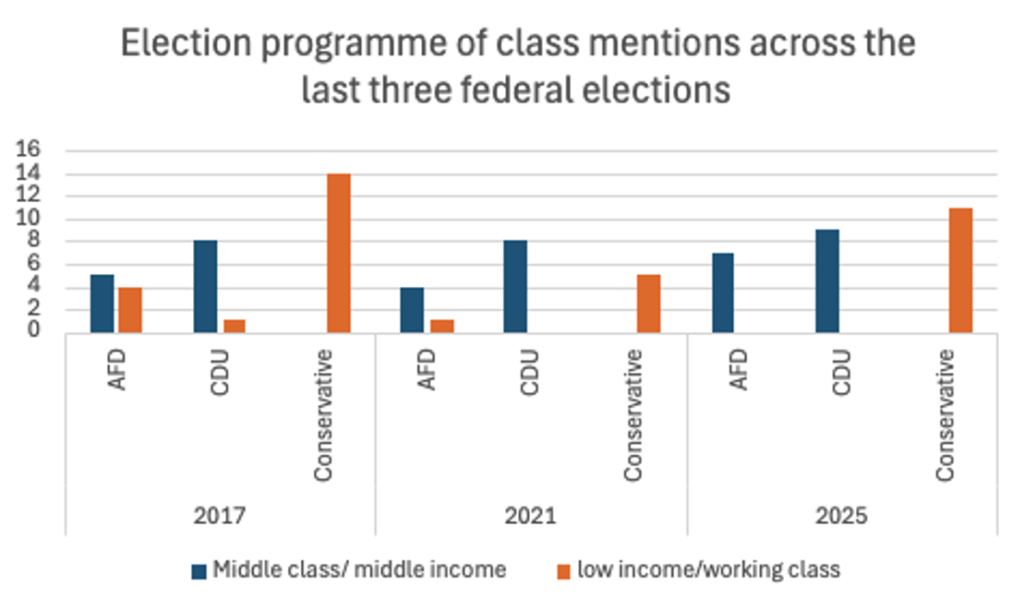

This phenomenon is not exclusive to Germany. In the United Kingdom, the Conservative Party has similarly directed its messaging towards working-class voters while enacting policies that favour the wealthy. Figure 1 demonstrates occurrences of class-based focus within the party program or manifesto. This rise in class-based rhetoric coincides with growing economic insecurity. However, this does not translate into substantive policy benefits for lower-income groups, raising questions about the sincerity of these political appeals.

Figure 1 demonstrates how often the three selected parties mention working class or middle class. The primary sources were official party manifestos and election programs from 2017, 2021, and 2025 (for CDU and AfD) and from 2017, 2019, and 2024 (for the UK Conservative Party). The keywords selected were Mittelstand (middle class), Mittelshicht (middle class), Mittlere Einkommen (middle income), Arbeiter (worker or working class), and Untere Einkommen (lower income), chosen to reflect direct class-based appeals. A systematic content analysis was performed using keyword frequency counting within official party programme PDF texts and manifesto materials. Quantitively tracked the frequency of class-related terms, with the aim of measuring how often parties mentioned representing the interests of the middle or working class across several election cycles.

Descriptive vs. Substantive Representation: The Politics of Perception

While data shows that class-based rhetoric is increasing, how do we explain this phenomenon in theoretical terms? Pitkin’s concept of representation provides a useful framework for understanding the gap between political messaging and actual policy outcomes. Political theorist Hanna Pitkin differentiates between descriptive representation—where politicians physically or socially resemble those they represent—and substantive representation, which refers to actual advocacy for a group’s interests10. Pitkin boiled the two concepts down very simply to; descriptive representation meaning “standing for”11 versus substantive representation as “acting for”12. Descriptive representation entails politicians sharing demographic traits or experiences with their constituents. Whereas substantive representation politicians advocating for policies that truly benefit their constituents. While politicians like Merz and Weidel claim to “stand for” the middle class descriptively, their policy positions suggest they fail to “act for” them substantively13.

CDU leader Friedrich Merz, for example, publicly identifies as “upper middle class,” despite having an annual salary exceeding one million euros14. Similarly, Alice Weidel of the AfD, a former investment banker with a PhD, portrays herself as a champion of Germany’s struggling middle class15. Their voting records and policy positions, however, suggest a strong preference for protecting wealth and reducing social benefits rather than advocating for the socio-economic groups they claim to represent.

Who would you trust to best represent your interests? A politician who may have grown up with the same experiences as you? Someone who claims to understand your experience.

The German Bundestag is not representative of their own population, those who have attained a low or middling level of education are hugely underrepresented16. Studies completed by Lea Elsässer et al have found that those from upper social classes disproportionately impact policy outcomes17. This means for most German citizens who don’t fit into the upper social classes, locating a politician who is capable and willing to substantively represent them is vital.

Political Leaders: Champions of the People or Protectors of the Elite?

Friedrich Merz (CDU): Claims to represent middle-class values, yet his background in investment banking and million-euro salary suggest otherwise. His policy focus includes reducing social welfare benefits and opposing a wealth tax18.

Alice Weidel (AfD): Positions herself as an advocate for the middle class, by discussing the “suffering” of the German middle class caused by the mainstream parties’ actions19. Weidel has publicly warned of the “bankruptcy” of the middle class while advocating tax cuts that primarily benefit high-income earners20.

Kemi Badenoch (UK Conservative Party): Uses rhetoric focused on opportunity and self-reliance while opposing progressive identity politics and advocating for strict immigration controls21. Her background in finance and privileged upbringing contrast with the working-class image she projects22.

How Politicians Exploit Discontent

Income inequality has increased in Germany, with the richest 10% owning 56% of total wealth23. Economic concerns such as taxation, industry investment, and welfare expenditure are crucial in the current political landscape.

Despite this, politicians’ claims of representation often obscure policies that favour the wealthy. This discrepancy leads to lower political trust and engagement, as voters feel misled by parties that promise support but fail to deliver substantive benefits.

The Role of Economic Inequality and Political Trust

How Income Inequality Affects Political Preferences

The CDU and AfD capitalize on voter frustration with mainstream parties, positioning themselves as champions of ‘ordinary people’ against political elites24. However, their policy proposals—such as CDU’s plan to abolish citizens’ allowance and reject a wealth tax—suggest their commitments to social equity are questionable25.

Political inequality is further entrenched when voters support parties that do not substantively represent their interests. Economic hardship often leads voters to seek simple, emotionally charged solutions, making them more susceptible to rhetorical appeals rather than policy scrutiny26. This reinforces existing power structures where elites maintain control while securing votes from disenfranchised groups.

Voting Behaviour and Political Trends

Growing Support for Right-Wing Parties Among Workers

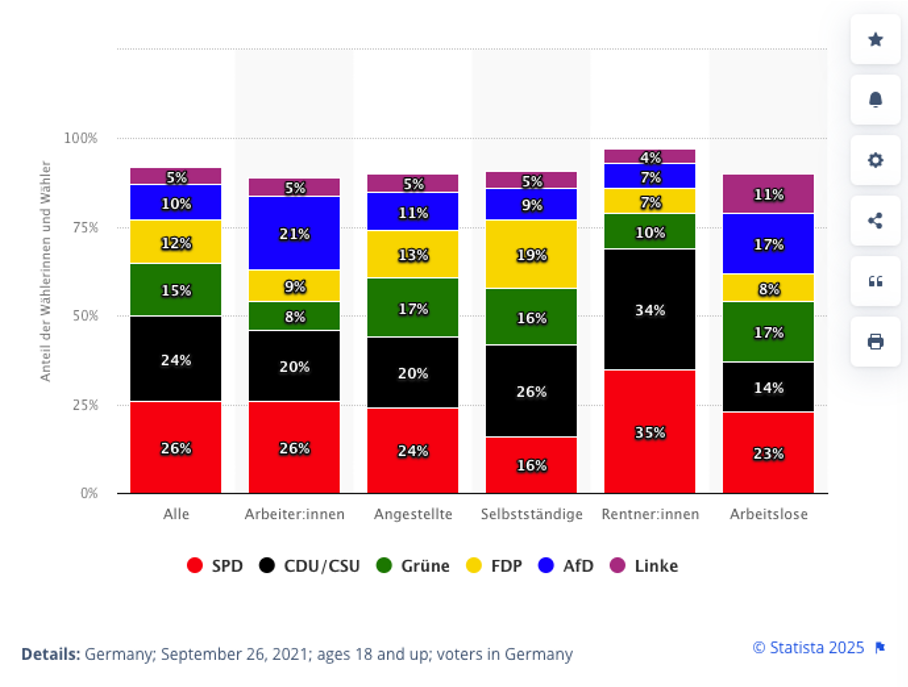

Despite their policies favouring the wealthy, the AfD has gained increasing support among workers and trade union members. The 2021 federal elections showed a shift in worker support from traditionally left-wing parties (such as the SPD) to the CDU and AfD27.

Figure 2 demonstrates the “Voting behaviour in the Federal Election on 26th of September 2021 by employment/activity”28. Figure 2 is based on voting behaviour statistics from ARD and Statista, which track voter turnout and preferences by employment status. The sample includes voters categorized by employment type (e.g., blue-collar workers, white-collar employees, public sector workers, and self-employed individuals).

Traditionally, blue-collar and industrial workers supported the SPD due to its historical ties to trade unions and labour protections29. However, the data shows a significant drop in SPD’s support, indicating disillusionment with mainstream left-wing policies. The AfD has gained a notable share of worker votes, particularly in industries affected by economic stagnation and globalization. While CDU’s rhetoric suggests an increased focus on the middle class, the party’s actual voter base remains strong among white-collar professionals and business owners, reinforcing the argument that its policies favour economic elites. The realignment of worker votes toward CDU and AfD suggests a growing disconnect between economic interests and voting behaviour. Right-wing rhetoric effectively mobilizes economic grievances, even when policy outcomes do not favour lower-income voters. The AfD has successfully marketed itself as the party of ordinary people, despite policies that disproportionately favour the wealthy. They offer change through their antiestablishment position. This paradox reflects a broader trend in European politics, where populist rhetoric often conceals elite-driven economic agendas.

Why it is working?

Mainstream parties’ failure to address economic concerns: As economic disparities grow; disillusioned voters turn to alternative parties that claim to address their struggles.

Many voters feel ignored by traditional political figures, making populist messaging more appealing. Recent election data from the European Parliament and varying state elections, demonstrates a surge in popularity amongst workers for the AfD, this can be seen in Figure 330. A visible shift in worker support towards CDU and AfD indicates growing disenchantment with mainstream parties like SPD. This aligns with research on economic voting behaviour—where voters support parties that appear to address economic grievances, even if their policies contradict working-class interests.

Figure 3 depicts vote share by different occupation31. Figure 3 is derived from federal election exit polls, tracking vote share by occupation rather than just employment status. The sample includes votes from manual labourers, service workers, small business owners, and unemployed voters. A comparative approach was used to evaluate which occupational groups favour right-wing parties. The figure highlights unexpected trends; such as AfD’s success among service-sector workers and the unemployed, groups traditionally aligned with left-wing policies. Despite advocating for tax cuts favouring high earners and reductions in social benefits, the AfD has gained traction among economically vulnerable groups. This can be explained by the SPD, traditionally associated with social safety nets and worker protections, losing support from unemployed voters, suggesting a failure to address economic anxieties effectively.

Beyond the Rhetoric: How Political Inequality Shapes Germany’s Future

Friedrich Merz (CDU): States concern for struggling citizens but supports eliminating key welfare benefits. Merz proposed lowering corporate taxes and simplifying the tax system. To achieve this some social service funding may need to be cut32. The CDU manifesto mentions “abolishing” the citizen’s allowance33. The manifesto also calls to reject a wealth tax. The contradictory planning in investment and spending cuts from the manifesto are geared towards ensuring wealth inequality grows. Whilst there are issues with the citizens allowance, it serves 5.5 million people to be kept out of poverty in Germany. Only 0.27% of whom are calculated as “total refusers” of work34. Merz has also been quoted saying “many people in this country are up to their necks in debt”, if so, why not support a sufficient welfare policy to provide protection against such vast inequality35?

Alice Weidel (AfD): Claims to support the middle class but advocates tax cuts that weaken social safety nets36. According to a Federal Government secure income report, money partially raised through taxation supports the continuation of welfare programs that prevent the appearance of absolute poverty as opposed to relative poverty in Germany37. (Generally speaking) There is no absolute poverty in Germany today according to the Federal Government, the basic means tested ‘safety net’ prevents this absolute poverty38. The AfD have consistently advocated against a minimum wage and supports reducing welfare benefits39. If the findings of the ’secure income’ report are to be believed, then such actions could significantly erode the quality of life of lower-income groups.

The ZEW Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research indicated that AfD and CDU policies disproportionately benefit the wealthy and exacerbate income inequality40. This can have a detrimental effect on engagement and trust in the German political system. Cutting welfare programs and unemployment benefits significantly increases economic uncertainty for lower-income citizens. The likely outcome of this is a deepening of structural inequality41.

The Political Reality Behind Class-Based Messaging

While political rhetoric is an essential tool for mobilizing voters, it is crucial to analyse policy actions rather than campaign promises. The CDU and AfD strategically position themselves as representatives of the middle and working class, but their economic policies suggest otherwise. Voters should critically assess whether politicians act in their best interests or merely claim to do so for electoral gain.

As voters navigate these political messages, critical scrutiny of both rhetoric and policy is essential. The upcoming Bundestag election offers a pivotal moment to demand not just representation in words, but action in policies that genuinely reflect the needs of the people.

References

1 “Neueste Wahlumfrage zur Bundestagswahl von Forsa”, Dawum, 4th February 2025. https://dawum.de/Bundestag/Forsa/ Accessed 10th February 2025.

2 Ibid.

3 Havertz, Ralf. “Strategy of Ambivalence: AfD between Neoliberalism and Social Populism.” Trames 24, no. 4 (2020): 549-565. Page 550.

4 Keir Starmer, Labour Party . April 16th 2024. https://labour.org.uk/updates/stories/watch-keir-starmer-party-election-broadcast-background-changing-politics/ Accessed 14th February 2025.

5 Regniet, Thomas. 02.02.2025. WirtschaftsWoche, “These alternatives are already available in advance”. https://www.wiwo.de/politik/deutschland/wahl-o-mat-diese-alternativen-sind-bereits-vorab-verfuegbar-/30193140.html

6 Brady, Henry E., Sidney Verba, and Kay Lehman Schlozman. “Beyond Ses: A Resource Model of Political Participation.” The American Political Science Review 89, no. 2 (1995): 271–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082425. Page 273.

7 Havertz, Ralf. “Strategy of Ambivalence: AfD between Neoliberalism and Social Populism.” Trames 24, no. 4 (2020): 549-565. Page 550.

8 Schindler, Frederik and Alexander, Robin. “There is absolutely no reason for moderation”. 26th August 2024.

9 Weidel, Alice. 2022. https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2022/kw52-interview-afd-926028

10 Pitkin, Hanna F. The Concept of Representation. United Kingdom: University of California Press, 1967. Page 142.

11 Pitkin, Hanna F. The Concept of Representation. United Kingdom: University of California Press, 1967. Page 92.

12 Pitkin, Hanna F. The Concept of Representation. United Kingdom: University of California Press, 1967. Page 126 and Page 114.

13 Pitkin, Hanna F. The Concept of Representation. United Kingdom: University of California Press, 1967. Page 126 and Page 92.

14 Böcking, David and Hesse, Martin. “Why Merz is not part of the middle class” Spiegel Business. 15th November 2018. https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/friedrich-merz-warum-er-nicht-zur-mittelschicht-gehoert-a-1238635.html

15 Bundestag Biographies, 2022 https://www.bundestag.de/webarchiv/abgeordnete/biografien19/W/524466-524466

16 Lea Elsässer, Svenja Hense & Armin Schäfer (2021) Not just money: unequal responsiveness in egalitarian democracies. Journal of European Public Policy, 28:12, 1890-1908, DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2020.1801804 Page 1894.

17 Ibid.

18 ZEW. “Reformvorschläge der Parteien zur Bundestagswahl 2025: Finanzielle Auswirkungen”, Leibniz-Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung, January 17, 2025, https://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/gutachten/Bundestagswahlprogramme_ZEW_2025.pdf Page 6.

19 Alice Weidel in conversation with Volker Finthammer. 2022. https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/alice-weidel-afd-ukraine-krieg-100.html Accessed 18th January, 2025.

20 Weidel, Alice. 2022. https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2022/kw52-interview-afd-926028 Accessed 18th January 2025.

21 Badenoch, Kemi. 17th November, 2024. https://www.conservatives.com/news/kemis-speech-about-immigration

22 Hope, Christopher. “Kemi Badenoch hails Reform UK voters as ‘our people’ – before taking huge swipe at Farage”. Chopper’s Political Podcast. GB News. Accessed 15th February 2025.

23 WZB Berlin Social Science Center. Press release “Inequality and risk of poverty have hardly changed – despite rising wealth and wages”. 6th November 2024. https://www.wzb.eu/de/pressemitteilung/ungleichheit-und-armutsrisiko-kaum-veraendert-trotz-steigender-vermoegen-und-loehne

24 Benoit, Bertrand. Wall Street Journal. (2025) ‘Meet the Blue-Collar Voters Making Germany’s AfD Mainstream’, The Wall Street Journal, 4th February 2025.

25 CDU. Party program, 2025. https://www.cdu.de/wahlprogramm-von-cdu-und-csu/

26 Bartels, Lorry. “Economics Still Matters to Poorer Voters.” Challenge 51, no. 6 (2008): 38–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40722545. Page 39-40.

27 ARD. Wahlverhalten bei der Bundestagswahl am 26. September 2021 nach Tätigkeiten (Stimmenanteile der Parteien). Chart 27. September 2021. Source Statista.

28 ARD. Wahlverhalten bei der Bundestagswahl am 26. September 2021 nach Tätigkeiten (Stimmenanteile der Parteien). Chart 27. September 2021. Source Statista.

29 Ibid.

30 Schläger, Catrina/Katsioulis, Christos/Engels, Jan Niklas (2024): Analysis of the 2024 European elections in Germany. Majority for the stable center despite strong right-wing fringe. In: FES diskurs, n.o. (Bonn), p. 10. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/a-p-b/21287.pdf

31 Ibid. Page 11.

32 Crossland, Davis. “Friedrich Merz’s economic cure for Germany, the sick man of Europe”. The Times. 12th January 2025. https://www.thetimes.com/world/europe/article/friedrich-merz-agenda-30-germany-economic-plan-6xz8qnd3g?utm_source=chatgpt.com®ion=global

33 CDU. Election program, 2025. https://www.cdu.de/wahlprogramm-von-cdu-und-csu/

34 LB BW. Germany’s contentious social benefits. Source: Federal Employment Agency, LBBW Research. 31st January 2025. https://www.lbbw.de/article/to-the-point/fact-checking-germanys-social

35 Bundestag (23.11.22) https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2022/kw47-de-generalaussprache-918180

36 Kim, Juho. The radical market-oriented policies of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and support from non-beneficiary groups – discrepancies between the party’s policies and its supporters. Asian j. Ger. Eur. stud. 3, 6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40856-018-0028-7

37 Die Bundesregierung. “Government Report on Wellbeing in Germany”. https://www.gut-leben-in-deutschland.de/report/income/ Page 96.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 ZEW. “Reformvorschläge der Parteien zur Bundestagswahl 2025: Finanzielle Auswirkungen”, Leibniz-Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung, January 17, 2025, https://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/gutachten/Bundestagswahlprogramme_ZEW_2025.pdf Page 9.

41 Stiglitz, J. (2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future. W.W. Norton. Page 397.