As the federal elections in Germany approach, we’re excited to share a series of three blog posts on topics related to the election. All three posts are written by students from one of Eva Wegner’s courses. This post is the third and last in the series.

Authors: Merle Ecker, Johann Mecklenburg, Miriam Schießl, and Alexander Watt

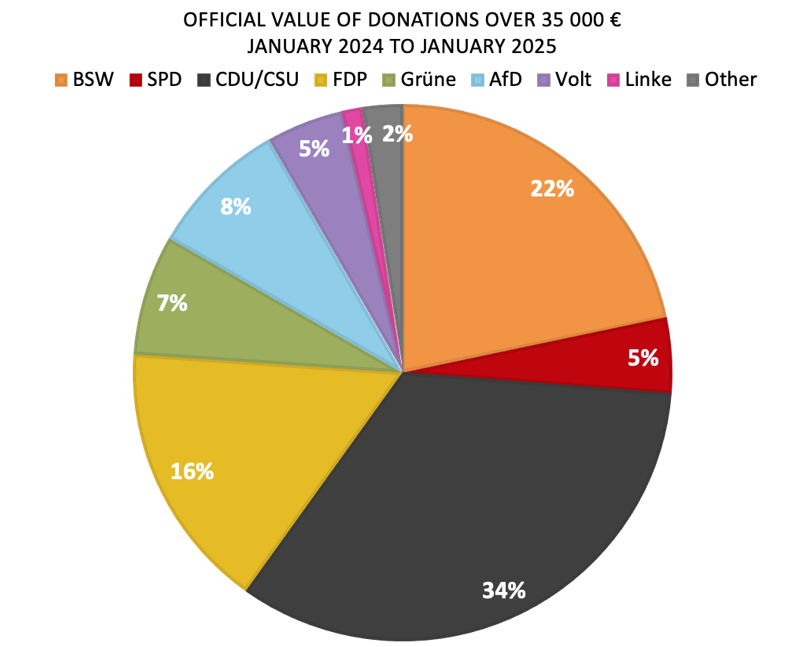

On 23rd of February 2025 national elections will be held in Germany and enormous amounts of money have been donated to parties. In mid-January 2025, the AfD received the highest donation in its history until that point. Winfried Stöcker, a businessman and multimillionaire donated 1.5 million Euros to the far right-wing party1. This was even exceeded last week: 2.4 Million euros arrived in the bank account of the AfD, the highest donation in this election campaign was donated by a former right-wing politician from Austria. Gerhard Dingler says he is investing in peace. For several years the Austrian and German far-right have been supporting each other – another powerful alliance2. In 2024, German parties received over 18.62 million Euros of large donations, Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) received 6.41 million Euros, Christian Democratic Party (CDU) was second with 5.3 million Euros3. This sudden increase in donations, at this scale, leaves some questions about the significance of income for political parties. How are parties funded? And how are party donations organized? What is their impact on political inequality?

We need this critical engagement because donations are not spread out equally between the parties and therefore inequality is created, before elections even start. In fact, it’s clear that donations from corporations to political parties are directly tied to their own desire to maximize their own profits4. And only successful companies and privileged private people are able to donate and therefore their interests are better represented: policy outcomes favour the rich. According to German law, parties need to make their donations transparent if they exceed 35,000 Euros since March 2024. The exact amount as well as names of donors are posted on the website of the Bundestag for example5.

But how is the funding of parties in Germany organized in general? Parties are mostly funded by the state, membership fees, and donations. The state funds every party that was voted for either in the last European or national elections by at least 0.5% of the population or was voted for by at least 1% in regional elections. For the first four million voters parties receive one Euro each and after that 83 cents per vote. For each euro donated and membership fees, the parties get an additional 45 cents from the state6. In general, parties would be able to exist without donations at all, but as soon as a few parties receive higher donations than others, an imbalance arises.

But concerning donations, there are some more rules. For example, donations from foreign countries are illegal if they exceed 1000 Euros. Anonymous donations of over 500 Euros are also illegal. Donations from public institutions (being at least 25% publicly owned) are forbidden as well. Hence, conflicts of interest are supposed to be avoided as well as double benefits. If a political foundation for example would donate money to a party, this would be unjust, as the party as well as the foundation receive funding from the state, and the state even gives the parties 45 cents for each euro that was donated to them. Like this, unfair advantages are created7.

Are all these rules creating political equality and equal chances for parties? Some political actors ask for general limitations on donations; Grüne (the Greens) and die Linke (the Left) no longer want to accept higher donations than 25,000 from private persons – at least that is what they say in their current party program. Die Linke additionally does not want to accept donations from companies in general to avoid further supporting capitalist logics8.

In general donations are not allowed to be earmarked9; but if the BMW heiresses (Susanne Klatten and Stefan Quandt) have donated over four million Euros to the CDU since 200210, they just might have an agenda and concrete reasons why they have not donated the same amount to Grüne. The discussions on party donations are ongoing and many critics and organizations such as Lobby control and Abgeordnetenwatch (an organization that tracks the parliament’s activities) continue to claim that corporate lobbying and the influence of the rich deepen inequality and skewer the political landscape in favour of the few, rather than the many11.

Official donations

Since the end of the traffic light coalition, and in the context of the election campaign more than 15 million Euros have been officially donated to the political parties. Most of the donors are businesses and private persons from various economic sectors12. In the past four national elections, donations have spiked drastically13. Donations have a significant financial role in the election14. Finance and the economy have become a key issue for the upcoming election, in particular with the influence of rich donors. As mentioned, people with more financial resources compared to those with less financial resources are able to make bigger donations, which gives them more impact on the campaign, the party’s opportunities, capital, and election success and possibly influence the post-election policies.

The graphs that are based on the data presented by the Bundestag15 clearly show the connection between the collapse of the coalition and the proceeding election campaigns with the amount of donations that have continuously increased since November 2024. This has particularly benefited parties that traditionally support a free market economy and thereby have a financial advantage in the elections: the FDP and the CDU16. Here, CDU has received the highest number of single donations over 35,000 Euros (95 times), followed by the FDP (45 times). The BSW is the main exception, where the donations correlate with the formation of the party rather than the election.

When donors predominantly support parties that favor free-market policies, it might impact the party’s policies to prioritize business and economic liberalization over social protections, potentially widening economic inequality and limiting the political influence of less wealthy citizens. Parties representing the wealthiest groups can accumulate funds, allowing them to run more extensive campaigns and gain a significant financial advantage in securing political power while remaining within their rights. This demonstrates that the regulations on donations are inadequate to ensure fair political competition.

| Top 5 official donors (November 2024 – January 2025) | ||||

| Donor | Number of donations | Value of donations | Party | |

| 1 | Bitpanda GmbH | 4 | 1 750 000€ | CDU/CSU (43%); FDP (29%); SPD (29%) |

| 2 | Prof. Dr. Winfried Alexander Stöcker | 1 | 1 500 000€ | AfD (100%) |

| 3 | Thadaeus Friedemann Otto | 1 | 1 000 000€ | Volt (100%) |

| 4 | Deutsche Vermögensberatung | 9 | 1 000 000€ | CDU/CSU (58%); FDP (25%); Green (8%); SPD (8%) |

| 5 | Dieter Albert Richard Morszeck | 2 | 1 000 000€ | FDP (100%) |

Between November 2024 (when the coalition collapsed) and January 2025, five major donors contributed at least one million Euros each. Among them are two companies and three private individuals. Deutsche Vermögensberatung and Bitpanda donated to multiple parties, presenting themselves as supporters of democracy across the political spectrum. Andreas Pohl, CEO of the German, Swiss, and Austrian consulting firm17, Deutsche Vermögensberatung, stated that the company has supported democracy and a free-market economy for decades18. However, a closer look reveals that the CDU/CSU and FDP were the primary beneficiaries of both donors. Bitpanda, an Austrian cryptocurrency advisory firm19, also made a significant contribution, with its founder describing it as a political statement to strengthen Germany’s “incredible transformation.”20 Given the relevance of cryptocurrency regulation in these elections21, corporate influence on legislation remains a critical issue.

Other notable donors include Professor Dr. Winfried Alexander Stöcker, founder of Euroimmun and owner of Lübeck Airport22, who gained attention for organizing unauthorized COVID-19 vaccinations. He also made the largest single donation to a political party within this timeframe to the AfD23. Thadaeus Friedemann Otto, heir to the Hausschus Haflinger fortune and a German rapper24, pledged to support Volt “with everything I own”25. Dieter Albert Richard Morszeck, CEO of Rimowa, sold 80% of the company for 640 million euros26, but did not disclose his motives behind his donation27. Whether in the name of their companies or as private people, these donations clearly demonstrate the impact of a few rich people. Wealthy individuals can disproportionately influence the political discourse, shaping policies in their favor while smaller donors lack comparable access. This financial imbalance creates an uneven playing field, where political influence is tied to economic power rather than public support. As a result, policies may increasingly reflect the interests of a few affluent donors rather than the broader electorate, undermining democratic representation.

Unofficial Donations

Yet the influence of the wealthy few on German politics is not limited to funding parties that best represent their interests. At most, official donations to political parties are a strategic measure hoping to create advantages for the corporate or individual donors through possible future policies. The particular rules around political party funding in Germany do however leave room for certain loopholes to be exploited by wealthy persons and groups. In collaboration with the parties, large businesses and lobbies have found a way to boost their direct influence on politics by circumventing donation laws, whilst also gaining access to executive politicians. At constitutional party conventions, political parties invite corporations, lobbies, and other financial entities to a “Messe”, where they can rent space for a stand at absurd prices 28.

The scale of this loophole is demonstrated in a report from Abgeordnetenwatch, which has assembled all known sponsors and presenters who have attended such a convention. Though not all received amounts have been made public, there are enough available reference prices that show just how lucrative this practice can be for the parties. For example, in 2019, Volkswagen and Audi paid 50,000 Euros to attend the SPD convention. They also attended the FDP and CDU conventions, but the amount paid has not been revealed29.

This already reveals the first issue with this dubious practice. As mentioned, since March 2024, the new limit for undisclosed donations is 35,000 Euros, before which it had been 50,000 Euros30. However, with this tactic, the FDP and CDU could have accepted the same amount as the SPD as a price of attendance, without having to publicize it. In fact, the only reason it is known that these businesses did pay to attend the 2019 convention, is that their stand was present and visible in photos and videos of the convention. This shouldn’t however suggest that we simply don’t know whether the CDU and FDP receive money, because we do. For example, Deutsche Bahn records show that it paid 220,000 Euros to attend SPD, CDU, CSU, and FDP conventions between 2013 and 202331. Of course, this method of funding is not for nothing. The businesses in question stand to benefit from their attendance by gaining direct access to the executive members of the parties, thus giving them an opportunity to influence politics at the highest level. This demonstrates a clear example of political input inequality, given that most Germans never get the opportunity to advocate for themselves directly to those meant to represent them. By attending the assemblies and conventions of multiple if not all major parties, wealthy groups are able to significantly skew the substantive representation of the country’s population in politics. Not to mention that the CDU went through a brief scandal, after it was revealed that they also offered personal conversations with their leadership as part of a convention attendance package, for 20,000 Euros32. A similar package was revealed to have been offered by the SPD before 2018. Since then, they have decided to principally publicize their convention rent income, as have the Greens33.

This evidence, again shows another problem with the practice. As mentioned, federally controlled businesses are not allowed to donate to political parties, however, Deutsche Bahn, and other private companies of which the government is a major shareholder, are sought out by the parties to attend their conventions as a lucrative source of income34. By disguising the transaction as an attendance fee rather than a donation, those involved are able to blur the line between conflict of interest, and advocacy in the interest of the German people.

Likewise, foreign businesses are not allowed to make major donations to political parties in Germany. Despite this, conventions choose to host representatives of foreign business interests for hefty fees, giving them access to influence the decision makers in the Bundestag. Most notably, international tech giants like Amazon, Google and Microsoft attend conventions for the FDP, CDU, and SPD regularly. Even more surprising perhaps, is Huawei’s attendance to these conventions. The Chinese telecommunications company was most recently present at the 2021 FDP national convention, although it is now understood that all major parties are choosing to distance themselves from Huawei, and no longer inviting them to such events35. Once again, the only amount available for reference is the 21,000 Euros Huawei paid to the SPD in 2019.

The result of this practice, in each problematic dimension, is that it ultimately incentivizes political parties to make concessions to corporations under more pressure than the law otherwise provided. Unregulated income from party conventions effectively circumvents the legal cap to financial advantage, as provided by corporations or wealthy individuals.

What does this imply?

While some donors aren’t shy about their reasons for donating, i.e. to support their economic interests, others remain silent about their reasons for donating to certain parties. By looking at corporate donations to German political parties in the lead-up to this year’s national elections, we can clearly see examples of input and output inequality. In order to keep up with campaign financing, the voices of the wealthy are being prioritized over those of the majority, meaning that they become overrepresented. In turn, policy proposals reflect that overrepresentation favoring the rich. As a result, campaigns effectively become more of a financial race rather than a political one. The sharp uptick in large single donations to certain parties demonstrates this phenomenon as a scramble to achieve an advantage. The result is that parties are therefore incentivized to make concessions and provide access to those who can help fund them. From the perspective of businesses, this translates to buying political influence through official and unofficial means. The election outcome increasingly depends on the ideologies of rich donors and the parties’ stance on the free market and capitalism. The wealthy can help maintain the established parties and keep them reflecting their interests. In other words, clearly disadvantaging what they consider undesirable movements for change. The power of a very few in elections further deepens the gap between rich and poor in society. It is true that pressure is slowly being put on reducing the scale at which this method of financing is possible, however, the system remains far from being adequately regulated. As long as donations remain an effective way to reach a campaigning advantage, whether officially or through legal loopholes, fair political competition will not be possible.

References

1 Joswig, Gareth (2025), “1,5 Millionen Euro für die AfD: Unternehmer spendet Rekordsumme für rechte Hetze“, TAZ, available: https://taz.de/15-Millionen-Euro-fuer-die-AfD/!6064313/ [accessed 01.02.2025].

2 Brunner, Simone & Florian Gasser (2025), “Von den blauen Kameraden lernen. AfD und Freiheitliche stehen sich schon lange nahe. Die Achse Wien-Berlin bringt Vorteile für beide Seiten“, Die Zeit, Vol. 6, available: https://www.zeit.de/2025/06/afd-und-fpoe-parteispende-rechtspopulisms [accessed 07.02.2025].

3 Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (2025), “Parteienfinanzierung – Regeln für staatliche Finanzierung und Parteispenden“, available: https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/taegliche-dosis-politik/558780/parteienfinanzierung/ [accessed 01.02.2025].

4 Deutscher Bundestag (2025), “Parteispenden über 35.000 € – Jahr 2025”: available: https://www.bundestag.de/parlament/praesidium/parteienfinanzierung/fundstellen50000/2025/2025-inhalt-1032412 [accessed 01.02.2025].

5 Deutscher Bundestag (2024), “Parteispenden über 35.000 € – Jahr 2024”: available: https://www.bundestag.de/parlament/praesidium/parteienfinanzierung/fundstellen50000/2024/2024-inhalt-984862 [accessed 09.02.2025].

6 Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (2025), “Parteienfinanzierung – Regeln für staatliche Finanzierung und Parteispenden“, available: https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/taegliche-dosis-politik/558780/parteienfinanzierung/ [accessed 01.02.2025].

7 Stalinski, Sandra (2018), “Wann sind Parteispenden illegal?“, Tagesschau, available: https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/parteispenden-faq-101.html [accessed 01.02.2025].

8 Siever, Lara (2025), “Transparenz-Check der Parteien zur Bundestagswahl 2025“, Abgeordnetenwatch, available: https://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de/kampagnen/transparenz-check-der-parteien-zur-bundestagswahl-2025 [accessed 01.02.2025].

9 Stalinski, Sandra (2018), “Wann sind Parteispenden illegal?“, Tagesschau, available: https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/parteispenden-faq-101.html [accessed 01.02.2025].

10 Wölfl, Lisa & Martin Reyher (2024), “Die diskreten Milliardäre und ihre Wahlkampfspenden an CDU und FDP“, Abgeordnetenwatch, available: https://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de/recherchen/parteispenden/die-diskreten-milliardaere-und-ihre-wahlkampfspenden-an-cdu-und-fdp [accessed 01.02.2025].

11 Ibid.

12 Spieker, Greta & Sven Clausen (2025), “Geldsegen für CDU und FDP: So viele Großspenden gab es seit dem Koalitionsbruch“, RedaktionsNetzwerk Deutschland, available: https://www.rnd.de/politik/millionen-fuer-cdu-afd-und-co-wer-steckt-hinter-den-grossspenden-im-wahljahr-DA5CVS6ATVH43KNWU7M7LCSR7A.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

13 Nöstlinger, Nette & Cornelius Hirsch (2021), “Political party funding in Germany explained”, POLITICO, available: https://www.politico.eu/article/political-party-funding-in-germany-explained/ [accessed 2.2.2025].

14 Deckwirth, Christina (2021), “Die Macht des großen Geldes: Lobbyismus und Großspenden im Wahlkampf“, Lobbycontrol, available: https://www.lobbycontrol.de/reichtum-und-einfluss/die-macht-des-grossen-geldes-lobbyismus-und-grossspenden-im-wahlkampf-92921/ [accessed 2.2.2025].

15 Deutscher Bundestag (2024), “Parteispenden über 35.000 € – Jahr 2024”: available: https://www.bundestag.de/parlament/praesidium/parteienfinanzierung/fundstellen50000/2024/2024-inhalt-984862 [accessed 09.02.2025].

16 Clausen, Sven & Greta Spieker (2025),“Wie sich Wirtschaftspromis in den Wahlkampf einschalten“, RedaktionsNetzwerk Deutschland, available: https://www.rnd.de/wirtschaft/wahlkampfspenden-welche-parteien-von-der-wirtschaft-profitieren-H6R4P2NJLRH4FDUDEIZTV5REDM.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

17 Spieker, Greta & Sven Clausen (2025), “Geldsegen für CDU und FDP: So viele Großspenden gab es seit dem Koalitionsbruch“, RedaktionsNetzwerk Deutschland, available: https://www.rnd.de/politik/millionen-fuer-cdu-afd-und-co-wer-steckt-hinter-den-grossspenden-im-wahljahr-DA5CVS6ATVH43KNWU7M7LCSR7A.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

18 Clausen, Sven & Greta Spieker (2025),“Wie sich Wirtschaftspromis in den Wahlkampf einschalten“, RedaktionsNetzwerk Deutschland, available: https://www.rnd.de/wirtschaft/wahlkampfspenden-welche-parteien-von-der-wirtschaft-profitieren-H6R4P2NJLRH4FDUDEIZTV5REDM.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

19 Spieker, Greta & Sven Clausen (2025), “Geldsegen für CDU und FDP: So viele Großspenden gab es seit dem Koalitionsbruch“, RedaktionsNetzwerk Deutschland, available: https://www.rnd.de/politik/millionen-fuer-cdu-afd-und-co-wer-steckt-hinter-den-grossspenden-im-wahljahr-DA5CVS6ATVH43KNWU7M7LCSR7A.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

20 Clausen, Sven & Greta Spieker (2025),“Wie sich Wirtschaftspromis in den Wahlkampf einschalten“, RedaktionsNetzwerk Deutschland, available: https://www.rnd.de/wirtschaft/wahlkampfspenden-welche-parteien-von-der-wirtschaft-profitieren-H6R4P2NJLRH4FDUDEIZTV5REDM.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

21 Sims, Tom (2025), “What Germany’s election means for Bitcoin and the super rich”, Reuters, available: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/what-germanys-election-means-bitcoin-super-rich-2025-02-06/ [accessed 2.2.2025].

22 Spieker, Greta & Sven Clausen (2025), “Geldsegen für CDU und FDP: So viele Großspenden gab es seit dem Koalitionsbruch“, RedaktionsNetzwerk Deutschland, available: https://www.rnd.de/politik/millionen-fuer-cdu-afd-und-co-wer-steckt-hinter-den-grossspenden-im-wahljahr-DA5CVS6ATVH43KNWU7M7LCSR7A.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

23 MDR Aktuell (2025), “AfD erhält Großspende von 1,5 Millionen Euro von umstrittenem Arzt“, available: https://www.mdr.de/nachrichten/deutschland/politik/afd-grossspende-millionen-arzt-stoecker-102.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

24 Spieker, Greta & Sven Clausen (2025), “Geldsegen für CDU und FDP: So viele Großspenden gab es seit dem Koalitionsbruch“, RedaktionsNetzwerk Deutschland, available: https://www.rnd.de/politik/millionen-fuer-cdu-afd-und-co-wer-steckt-hinter-den-grossspenden-im-wahljahr-DA5CVS6ATVH43KNWU7M7LCSR7A.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

25 Volt (2024), “Großspende ermöglicht Volt Investionen in Wahlkampagne“, available:??https://voltdeutschland.org/bonn/neuigkeiten/grossspende-volt-deutschland [accessed 6.2.2025].

26 Spieker, Greta & Sven Clausen (2025), “Geldsegen für CDU und FDP: So viele Großspenden gab es seit dem Koalitionsbruch“, RedaktionsNetzwerk Deutschland, available: https://www.rnd.de/politik/millionen-fuer-cdu-afd-und-co-wer-steckt-hinter-den-grossspenden-im-wahljahr-DA5CVS6ATVH43KNWU7M7LCSR7A.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

27 Clausen, Sven & Greta Spieker (2025),“Wie sich Wirtschaftspromis in den Wahlkampf einschalten“, RedaktionsNetzwerk Deutschland, available: https://www.rnd.de/wirtschaft/wahlkampfspenden-welche-parteien-von-der-wirtschaft-profitieren-H6R4P2NJLRH4FDUDEIZTV5REDM.html [accessed 2.2.2025].

28 Reyher, M., (2024), “Lobbyismus auf Parteitagen: Google, Philip Morris, DFL: Das sind die Sponsoren der Parteien”, Abgeordnetenwatch.de, https://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de/recherchen/lobbyismus/google-philip-morris-dfl-das-sind-die-sponsoren-der-parteien [accessed 2.2.2025].

29 ibid.

30 Sarah, K., (2025), “Parteispenden: Was das Gesetz zu Spenden an Parteien vorgibt”, Anwalt.org, https://www.anwalt.org/parteispenden/ [accessed 2.2.2025].

31 Reyher, M., (2024), “Lobbyismus auf Parteitagen: Google, Philip Morris, DFL: Das sind die Sponsoren der Parteien”, Abgeordnetenwatch.de, https://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de/recherchen/lobbyismus/google-philip-morris-dfl-das-sind-die-sponsoren-der-parteien [accessed 2.2.2025].

32 Bank, H. (2010), Parteitags-lobbyismus aus Insider-Sicht, Lobbycontrol. https://www.lobbycontrol.de/aus-der-lobbywelt/parteitags-lobbyismus-aus-insider-sicht-3437/ [accessed 2.2.2025].

33 Reyher, M., (May 2024), “Lobbyismus auf Parteitagen: Google, Philip Morris, DFL: Das sind die Sponsoren der Parteien”, Abgeordnetenwatch.de, https://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de/recherchen/lobbyismus/google-philip-morris-dfl-das-sind-die-sponsoren-der-parteien [accessed 2.2.2025].

34 ibid.

35 Reyher, M., (May 2024), “Lobbyismus auf Parteitagen: Google, Philip Morris, DFL: Das sind die Sponsoren der Parteien”, Abgeordnetenwatch.de, https://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de/recherchen/lobbyismus/google-philip-morris-dfl-das-sind-die-sponsoren-der-parteien [accessed 2.2.2025].