Eva Wegner and Lukas Rädle

Beyond outright corruption, politicians often navigate a web of potential conflicts of interest. They accept campaign donations from lobbyists and private donors, transition into lucrative post-politics careers with the very industries they once regulated, and own assets that can be directly impacted by the policies they craft. A legislator who owns real estate might resist rent control, just as a wealthy politician may push to abolish inheritance taxes. Another legislator who depends on donations from the mining industry for their campaign might advocate for lowering environmental requirements for that industry. Even if no laws are broken, these situations can erode public trust by making it appear that policy decisions serve private interests over the public good.

While some level of financial entanglement is inevitable—politicians are, after all, private citizens with careers and investments—the fundamental question remains: how can one reduce incentives to shape policies for personal financial gain? One of the biggest problems is the lack of transparency. Transparency allows the public to hold politicians accountable and can provide incentives to pursue public, rather than private, interest.

In our project, “Politicians, policies and the reproduction of wealth” we study the relationship between financial self-interest and pro-wealth policies in four democracies, Brazil, Germany, South Africa, and the UK. In this blog, we discuss two major transparency gaps and how they vary in these countries: the undisclosed personal financial interests of politicians and their interactions with lobbyists.

Personal financial interest

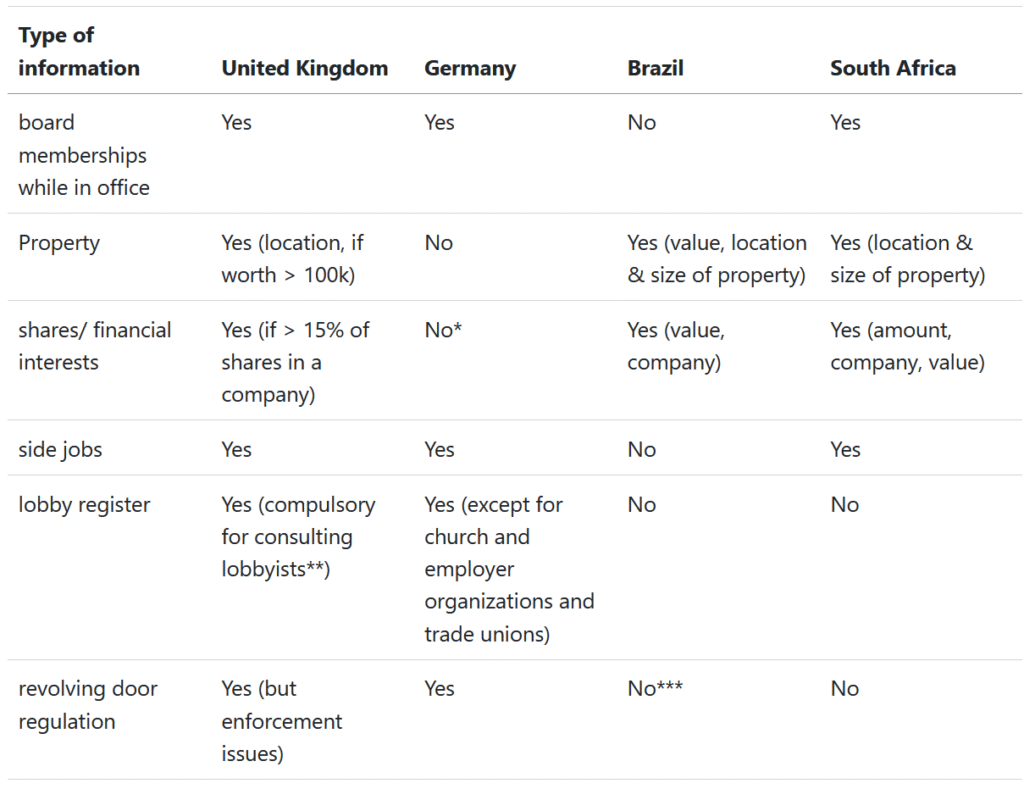

Most democracies require politicians to disclose some form of financial interest, but the level of transparency varies dramatically. Some countries mandate detailed declarations, while others leave much hidden from public view—creating a system where conflicts of interest can go undetected. At the same time, detailed disclosures (e.g., real-estate information) can raise legitimate privacy and safety concerns, so some systems use thresholds, redactions, or aggregation to balance transparency with personal security.

Consider two members of parliament (MPs) from different democracies, both serving in their governing parties. A South African MP is required to disclose extensive financial details, including real estate holdings, stock investments, trusts, board memberships and income from outside employment. A German MP, on the other hand, only needs to report side jobs or board memberships held during their term—leaving assets like property and stock ownership completely off the record.

Both MPs have the power to legislate on issues that could directly impact their financial interests, from property taxes and rent caps to corporate tax rates, industry subsidies, and regulations on businesses they may own or invest in. The difference? The South African MP’s financial interests are open to public scrutiny, allowing voters and watchdogs to assess potential conflicts of interest. The German MPs’ financial dealings are mostly opaque and shielded from oversight and making it difficult to know whether their policy decisions serve the public or their own portfolios. The UK and Brazil fall somewhere in between, but are both closer to South Africa than Germany in their disclosure requirements.

Having information on MPs assets is important for understanding potential conflicts of interests. For example, the generally progressive German laws about tenancy, such as, importantly the rent cap laws (from 2015 and strengthened in recent years), contain a loophole that allows landlords to evade rent control by labeling apartments as “temporary” and “furnished,” enabling them to charge significantly higher rents which has led to skyrocketing rents in big cities such as Berlin (The Guardian 2025). In South Africa and the UK, we would be able to know whether MPs have property in cities where this loophole has a strong effect on the rental market. We could also inquire which legislators might have been pushing for introducing this exemption into the law. In Germany, this is difficult.

(*only recorded in non-public minutes AND only if MP owns > 5% of shares of that company AND only if something related to that specific company (not the sector) is debated in a committee)

(**Consultant lobbyists refers to lobbyists that professionally work for third-parties, meaning lobby agencies or self-employed lobbyists. Others are called “in-house” lobbyists.

(***While there are revolving-door rules for MPs, there are cooling-off restrictions for senior officials in the federal executive branch.)

Lobbying

While German politicians face minimal financial disclosure requirements, their interactions with lobbyists are regulated far more strictly than in South Africa, Brazil, or the UK. However, this level of scrutiny is a recent development.

Before 2021, lobby groups in Germany could voluntarily enlist in a public registry with the Bundestag, which led to the listing of about 2,000 organizations. That changed after a series of political scandals involving high-ranking officials and led to the introduction of a mandatory lobby register. Interest groups must disclose their lobbying targets, areas of interest, spending, and clients. Lobbyists must specify which laws they seek to influence and report their budgets, including membership fees. Agencies lobbying on behalf of clients must make their affiliations public.

The two key reforms addressing transparency concerns about politicians’ interests in interactions with lobbyists are first, the mandatory recording of contacts (including heads of units in ministries) and second, transparency about the revolving door: politicians who move into industry jobs after leaving office must be registered as lobbyists.

In contrast, South Africa has no formal lobbying regulation, and Brazil has no lobby registry. While Brazilian MPs are obliged to disclose their schedules and official meetings with private individuals, lax enforcement means much lobbying influence still escapes public scrutiny.

The UK falls somewhere in between. Its statutory regime (ORCL) covers only consultant lobbyists—those working professionally for third parties, to register. However, this excludes “in-house lobbyists” who lobby on behalf of their employers, such as corporations or NGOs. As of Dec 2024, the voluntary UKLR listed about 1,251 registrants, versus 213 on the statutory ORCL (Mar 2024). These counts aren’t directly comparable, but they illustrate the scope gap. Consistent with that gap, a commonly cited estimate suggests consultant lobbyists account for ~4% of overall lobbying activity (Geoghegan 2025). Still, update schedules matter: Germany’s lobby register is supposed to be near-real-time (immediate changes; annual financials), whereas in the UK, consultant lobbyists file quarterly returns to the register.

The absence of a robust lobby register in these three countries is problematic. This problem can be illustrated by showing some insights provided by the new lobby regulations in Germany. First, the number of organizations registered as lobbyists almost tripled relative to the amount registered voluntarily before, growing from roughly 2,300 entries on the former voluntary list (Apr 30, 2020) to 7,164 published entries in the mandatory Lobbyregister (Jan 1, 2025). Second, the biggest players in Germany’s lobbying scene are the financial sector, banks, insurance firms, and investment companies that employ 442 lobbyists out of a total of 27,000, with an annual lobbying budget of €40 million (Finanzwende 2025). Third, it provides detailed information about potential revolving door effects: currently almost 700 lobbyists are former ministers, MPs, or high ranking government employees. The lobby register shows who and what they are lobbying for and allows investigations into how former legislative activities might be linked to these new careers [see Lobbyregister].

For researchers, journalists, and the general public, this has strong implications. In countries with robust financial disclosure systems and lobby registers, we can ask and empirically assess a number of questions that concern the personal financial interests of politicians. For instance: How has politicians’ wealth evolved during their time in office? Do they disproportionately benefit from subsidies or tax policies they’ve championed? Are they accumulating assets in areas where they influence legislation? Which type of lobbyist are they having meetings, with and how does subsequent legislation align with the positions of that group?

The absence of such data undermines democratic accountability, making it harder to hold politicians accountable for conflicts of interest and furthering detachment from politics. An increasing challenge in that area is the rise of wealthy, businesspeople-turned-politicians. These individuals often have strong incentives to avoid full disclosure of their financial interests, as doing so could reveal potential conflicts of interest or strategies to increase personal wealth through public office. For example, Friedrich Merz, Germany’s current chancellor, then an MP, filed a lawsuit in 2006 against the regulations requiring disclosure of side jobs, although the lawsuit was ultimately unsuccessful. This dynamic undermines accountability, allowing private interests to influence decision-making while eroding confidence in democratic institutions.

References

Finanzwende 2025: Mehr Klarheit über die mächtige Finanzlobby, Online: https://www.finanzwende.de/themen/finanzlobbyismus/mehr-klarheit-ueber-die-maechtige-finanzlobby [Last Access: 31.01.2025].

Institute for Government 2023: Eric Pickles is right: the rules for post-government jobs do not work, Online: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/eric-pickles-rules-post-government-jobs [Last Access: 31.01.2025].

Lobbyregister 2025: Statistik: Tätigkeitskategorien, Online: https://www.lobbyregister.bundestag.de/startseite/tatigkeitskategorien-statistik [Last Access: 31.01.2025].

Lobbypedia 2025a: Lobbyregister Deutschland, Online: https://lobbypedia.de/wiki/Lobbyregister_Deutschland [Last Access: 31.01.2025].

Lobbypedia 2025b: Lobbyregister Großbritannien, Online: Deutschland, https://lobbypedia.de/wiki/Lobbyregister_Gro%C3%9Fbritannien [Last Access: 31.01.2025].

Peter Geoghegan 2025,UK: Labour and the lobbyists, Online: https://mondediplo.com/2025/02/06uk [Last Access: 31.01.2025].

The Guardian 2025: The strange loophole that transformed Berlin from tenant’s paradise to landlord’s playground, 22.Jan. [Last Access 21/2/2025]. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/jan/22/berlin-housing-crisis-germany-rents-flats

UKLR 2025: About, Online: https://lobbying-register.uk/about/ [Last Access: 31.01.2025].