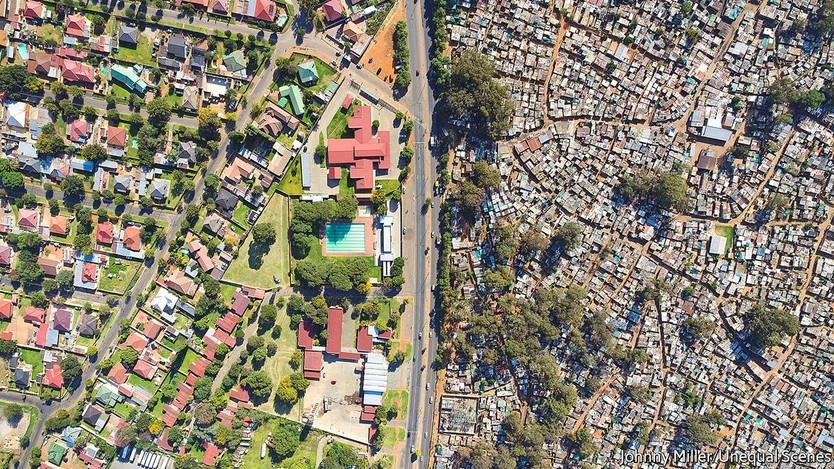

Pictures of inequality such as the one below have become widespread. They show different worlds coexisting side by side. These differences are visually striking but they are arguably more so when one considers the contrast in lived experiences that they imply: differences in income of course, but also often in health outcomes, educational opportunities, and crime rates and more generally life experiences: what happens when it rains heavily and when it is hot, when the time of the evening meal or the end of the month approaches. And it’s not only about lived experiences and welfare, it is also about how we interact with others: about power, respect, and control over one’s life. In some countries these differences are very large and particularly shocking, but even in countries where the differences are less extreme there are areas where one goes from a place that looks badly taken care of and even threatening to another that feels affluent and safe; it takes little effort to imagine stark differences in the way of life of its inhabitants.

These inequalities are at the same time the background and the outcome of politics. Policies can reduce inequality, as happened in Western countries after WWII and in Latin American countries in the 2000s. But policies can also reinforce and amplify inequalities, as the experience of Anglosaxon countries in the 1980s shows or, in an even more extreme way, Apartheid South Africa.

In democracies, citizens have a priori the possibility of affecting policy and thus to reduce many of the inequalities we experience. And a priori, it would appear that justice considerations, self-interest of non-rich citizens, and democratic accountability would make it just so.

But of course it is not so simple: justice considerations and self interest do not reliably lead to redistributive attitudes; redistributive attitudes do not necessarily lead to political action; and redistributive political action does not ensure that redistributive policies will be enacted and effective in reducing inequality. There are many crossroads and barriers in the path.

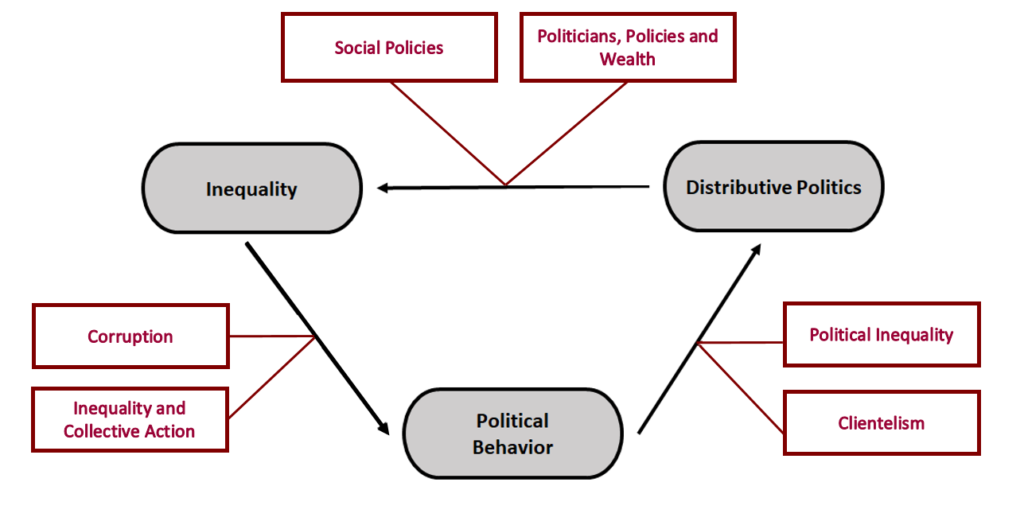

Moreover, the path does not go one way. Borrowing from our colleagues at the Politics and Inequality excellence cluster in Konstanz: citizen political attitudes and behaviors lead to policies that affect inequality, but inequality in turn affects citizens perceptions and attitudes. Inequality, political behavior, and distributive politics form a loop, and the outcome of this loop can determine the quality of our democracies and the fairness of our societies.

The research group Inequality and Distributive Politics, based at the University of Marburg, tries to understand some of this complexity. We study some of the barriers, crossroads, and interactions that characterize the link between inequality, political behavior, and distributive politics, as the figure below illustrates. In our research, we ask questions such as:

Why do poor citizens in the most unequal country in the world have only average demand for redistribution?

When do citizens sell their vote instead of voting for redistributive parties?

Which citizens do governments favor in their policymaking? Do politician connections to the elite bias their policymaking for the benefit of wealthy citizens?

Do education policies providing resources to disadvantaged schools improve student outcomes?

The puzzle of inequality and distributive politics starts with support for redistribution. Demand for redistribution can be surprisingly low in countries with high inequality. South Africa is a case in point. We studied this issue using survey experiments in different South African townships. We found that a sense of disempowerment can lead citizens to restrict their demand for redistribution: Citizens who are made aware that inequality in other countries is much lower, realize that high inequality is not inevitable and demand more redistribution from the state in terms of top taxes and social grants. In turn, citizens reminded of situations where collective action was successful, support protest that seeks more far-reaching change. You can read about this and other related research in the Inequality and Collective Action section.

Even if citizens, in principle, do support higher redistribution, it is not obvious that this will translate into political action. Usually, the most consequential political behavior to effect change in democracies is voting. But many non-rich citizens vote for parties or candidates whose platform is not about redistribution, regardless of their redistributive preferences. In many places, citizens “sell” their vote. Sometimes in the narrow sense that they truly receive a payment in exchange for their vote, or more generally by voting for someone that gives them some sort of personal benefit. This is the phenomenon of political clientelism which is widespread in many countries. Our project “The Demand Side of Clientelism” studies the experiences and choices citizens make in relation to political clientelism. We derived from the ethnographic literature different types of clientelism involving different experiences and welfare implications for citizens. And we studied these different types of clientelism via focus groups and surveys with experimental components in Tunisia and South Africa.

And even if citizens want redistribution and mobilize accordingly, it is not guaranteed that this will translate into inequality-reducing policies. Policymakers need to enact policies that represent the preferences of their voters. An emerging body of research has collected evidence that this is often not the case: enacted laws tend to be more consistent with the preferences of better-off citizens: in other words there is a considerable degree of political inequality. But almost all research about this is on European countries and the US. So we know very little about political inequality in other regions. Our new DFG project: “Unequal democracy in Brazil and South Africa” collects information on political inequality in these two countries. We do not simply replicate the work that has been done on the US and Europe. We argue that, when studying political inequality, it is not enough to look at whose preferences national level laws reflect; one also needs to consider policies at the local level: which neighborhood gets paved, which gets a clinic, which is well maintained. This is particularly important in poorer countries, but should also be investigated in richer countries like Germany. Moreover, even for the US and Europe, we know little about what may drive this type of political inequality. Our new VW-funded project “Politicians, Policies, and the Reproduction of Wealth ” studies the role of politician connections to the elite. We will conduct case studies in the UK, Germany, Brazil and South Africa. We will collect information on politician characteristics, track the role of specific politicians in the development of policies relevant for the wealthy, and study the implications of these policies for the incomes of the wealthy.

And finally, even if policies intended to reduce inequality are enacted, are they effective? We have studied education policies in South Africa and Zambia; policies that sought to provide resources to more disadvantaged schools. Using methods of causal inference such as regression discontinuity designs we have found little effect of the policies we studied: we believe that the amount of resources provided are too small to detect an effect in contexts where poorer schools suffer from cumulative disadvantages. In contrast, when we have evaluated discriminatory policies, such as the aggregate effect of South African Apartheid discriminatory policies, we have found a very large effect. Exploiting an exogenous change in racial classification we estimate the extent of white privilege as leading to a more than fourfold increase in income. You can read about our policy evaluation work on the Policies page.

But the story does not end here, there are feedback loops that can sustain very bad situations of high inequality, bad policy and disempowered citizens. Our collective action research indeed suggests that more inequality leads to more disempowerment, which leads to less demand for change, thus consolidating inequality. We also encounter feedback loops in research we conduct on corruption: anti-corruption policies can affect citizen’s very willingness to challenge corruption leading to potential vicious circles.

The main focus of our group is research, but we do not conduct the research for the sake of it. Our topic has a very clear social relevance and we are genuinely motivated by it, so we want to reach out to other researchers, to policymakers, and to the general public. We have three initiatives to articulate our outreach efforts. First, we publish every fortnight an IDP Research Digest. In this Digest, we collect five articles just published (in the previous two weeks) on inequality and distributive politics. The theme of inequality and distributive politics is varied and has different subtopics. But we want to counter the natural tendency of academia towards fragmentation and provide researchers interested in the overall topic a way to keep updated on contributions to the overall theme. Some focus is however necessary given our limited capacity, so we will focus mainly on political science publications. But we will cover literature both on the “Global North” and the “Global South”. We believe there is too much separation here too.

Second, we will publish a monthly blog. These blog entries will be research based. Sometimes we will show accessible versions of our papers; sometimes we will reflect on how the literature can help explain current events; or sometimes we will simply summarize literature we find interesting.

Third, we seek to engage with our local community and local government. We would like to bring research and information on inequality and distributive politics to the population and government of Marburg, and learn from them in turn. We have started to build a web resource to disseminate information on spatial inequalities in relation to politics in the form of maps for Marburg. Over time, we hope this resource will be more complete, encouraging citizens and local politicians to be more aware of the topic of inequality and distributive politics, and in that way work towards greater local accountability and fairness.