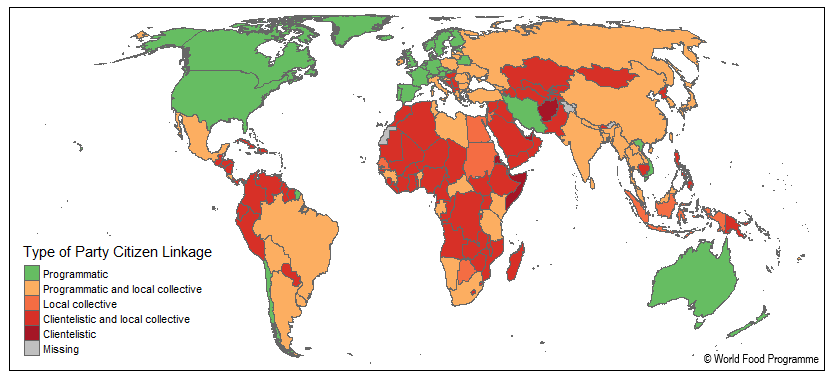

In most countries of the world, political parties do not use appeal to voters with programmatic promises – about the types of policies they would pursue when in office – but via promises of local public goods (such as wells, roads, or clinics) and or of fully particularistic goods (such as jobs or cash). As the world map below shows, exclusively programmatic appeals are only common in so called Western countries. In almost all other countries some combination of different linkage strategies prevails. Academics usually find clientelism normatively problematic. Most generally, because giving up political rights in exchange for access to goods undermines democratic accountability.

In addition, there are various other reasons why clientelism is seen as something negative. First, the particularistic nature of clientelism, as clientelism implies that some citizens get resources and others do not. Second, the disrespect or absence of transparent, formal rules for the allocation of scarce public resources. Third, distortions in the allocation of resources because resources are allocated to followers/clients for political support instead of need or merit. Fourth, the inequality in patron–client relationships as clientelism implies (to different degrees) a subordinate role of the client. If clientelism has so many negative features for citizens, why do they not opt out of it?

In our paper “What is bad about clientelism?”, published in Electoral Studies, we start with the observation that all these negative connotations of clientelism come from the academic literature that is rooted in Western normative perceptions of what is desirable and undesirable political behavior. At the same time, the citizens whose perceptions of the practice are crucial are those in communities where clientelism is prevalent. Ultimately, it is their experiences and perceptions that determine the persistence of clientelism. We address three questions. First, how do citizens in disadvantaged communities morally evaluate clientelism? Second, which aspects of clientelism do these citizens consider acceptable and unacceptable? Third, when considering clientelistic exchanges, do citizens evaluate the actions of fellow citizens differently relative to politicians? We explore these questions with conjoint experiments implemented in two poor communities in South Africa and Tunisia, and with academic experts that serve as a benchmark for the literature.

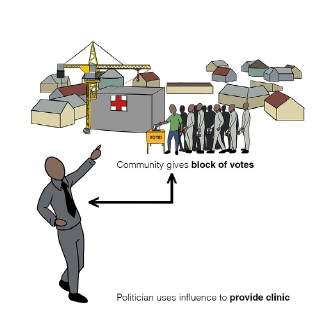

We build on recent literature on clientelism – including our own – that shows the existence of different types of clientelism that differ in the type of goods that are exchanged, the relationship between patron and clients, the amount of people who benefit and, ultimately, the welfare implications for citizens: Vote-buying is a form of clientelism that is characterized by low value exchanges (food, money for votes or turnout) and rather equal relations between clients and patrons. It is limited to exchanges during electoral campaigns. Relational clientelism consists of ongoing and potentially asynchronous exchanges between patrons and clients and goods of a higher value, such as, for example a patron helping a citizen to access healthcare and the citizen actively supporting the patron in a campaign. Traditional clientelism involves an exchange of insurance or other high value goods (such as jobs in the municipality) from the side of the patron and loyalty and subordination from the side of the citizen. In collective clientelism citizens exchange a block of votes in exchange for local public.

The types of clientelism link to different negative implications. With a larger beneficiary group, collective clientelism is less particularistic than the other forms of clientelism. The distortion in the allocation of resources is more pronounced in relational and traditional clientelism because the particularistic goods from the patron are of higher value. In turn, the inequality in the relationship between patrons and clients is highest in traditional clientelism and potentially lowest in vote-buying. These different implications imply different trade-offs and could lead to substantially different evaluations by citizens.

In our experiments, we vary the size of the beneficiary group, the degree of informality of the exchange, the inequality in patron-client relations, and two elements of distortions in public good allocation: the value of the goods, and the scarcity of the goods. We implement one experiment that varies the first two elements (size and informality) and a second, that varies the inequality and the different elements of distortion.

Because clientelism is a complex concept and the experiment was implemented in disadvantaged communities, we developed illustrations of the different dimensions of clientelism we wanted to vary in our experiment. The two illustrations below are examples of the first and second experiment. On the left hand side is an exchange where a community gives a block of votes to a politician, who, in turn, uses his influence to provide a clinic to the community (collective form of clientelism). On the right is an exchange where low value (bag of groceries for votes) yet scarce goods are exchanged, and the relationship between the politician and the citizen is equal (vote buying form of clientelism).

The experiment was implemented with 600 citizens in poor neighborhoods of Cape Town and Tunis who each evaluated six exchanges. In addition, we have a sample of around 100 academics who work on normative democratic theory or development who serve as a benchmark for the literature.

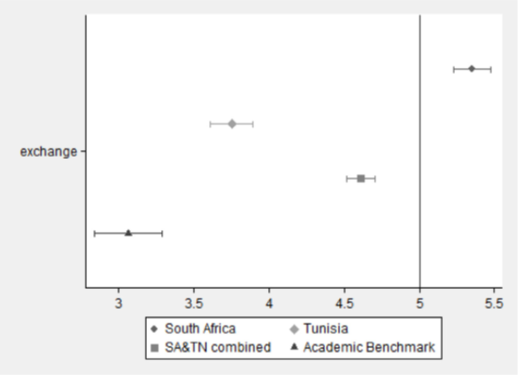

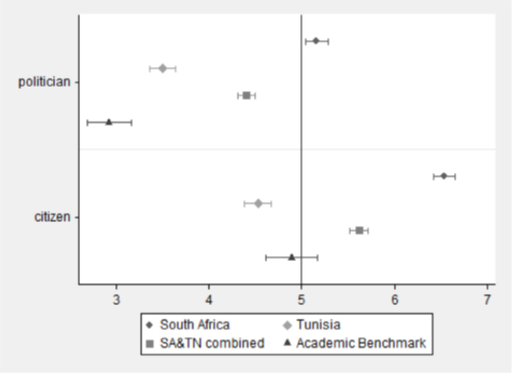

We find that respondents in Tunisia and South Africa overall find clientelistic exchanges considerably more acceptable than academic experts, in the case of South Africa almost 2.5 points more acceptable on a ten-point scale. We also find that the behavior of citizens in the exchange is seen in a much more positive light than that of the politician, suggesting that engaging in clientelistic transactions does not come with social sanctions for citizens.

Note: How acceptable is exchange. Scale ranges from 1-10 where ten is most acceptable.

Note: How acceptable is politician and citizen behavior in exchange. Scale ranges from 1-10 where ten is most acceptable.

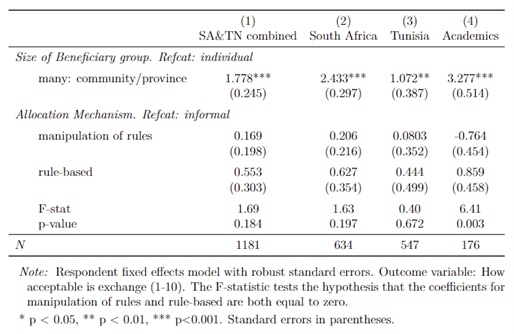

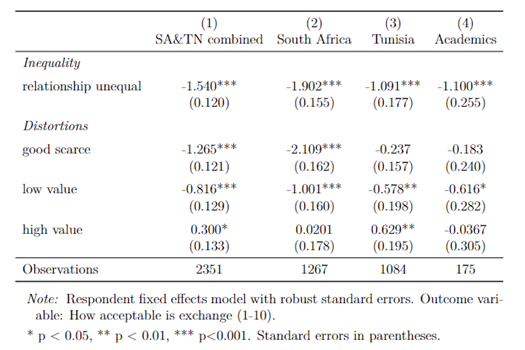

The size of the beneficiary group – essentially moving from individual forms of clientelism (relational, vote-buying, traditional) to collective forms – has a strong effect on evaluation (see table 1, below). On average, it increases the acceptability by around 2 points on the ten point scale. Also operating in the expected direction is the inequality of the relationship. Explicitly unequal relations in a clientelistic exchange matter a lot to respondents with effect sizes that are comparable, although a bit smaller, to the size of the beneficiary group (see table 2).

Other problematic dimensions of clientelism are less consensual among our respondents or operate in a different direction. The scarcity of a good only matters to South Africans, whereas rules only matter to Academics. Distortions coming from providing the client with a high value good are not seen as problematic. In contrast, what all respondents find less acceptable is when clients are receiving food to buy their vote, probably seen as an attempt to buy political support too cheaply.

Our findings provide relevant insights for the literature on the role of citizens for sustaining clientelism: citizens in communities where clientelism is prevalent might have few incentives to opt out of clientelism. They probably face little social cost for these practices in their communities. In contrast, the challenge for citizens might rather be to identify suitable patrons or brokers so that they can take part in the distributive benefits of clientelism. This is particularly true for types of clientelism that have little inequality, such as vote-selling or that have a larger beneficiary group, such as collective clientelism. Our findings suggest that the only form of clientelism that might generate higher social costs is a form of ‘‘traditional’ clientelism that is characterized by high inequality and the provision of scarce resources.

Our findings can also shed some light on why voter education campaigns against vote-buying have produced mixed results. A typical approach in recent campaigns is to emphasize citizen agency and the negative implications of vote-selling on public good provision. The findings from our paper would suggest that emphasizing citizen responsibility in clientelism is a delicate matter. According to our results, citizen behavior is seen as substantially more acceptable than politician behavior. Similarly, when exchanges were seen as unacceptable and respondents provided a reason for this judgment in open text evaluations, the blame was put more with the politicians, and less on the clients. More generally, our findings suggest that emphasizing the inequality often involved in clientelistic exchanges could be a fruitful avenue to designing campaigns that resonate with the values of citizens exposed to clientelism.