In our research, we seek to better understand the mechanisms of distributive politics. The first step of this venture often is to assess what part of a government body’s work actually is distributive in nature. First and foremost, this means determining what exactly it is responsible for and how independent it is in the implementation of those responsibilities. In my own work, I mostly focus on local politics. Therefore, in our third entry in the local spending series, I want to shine a light onto the topic of local government autonomy, and how it presents both challenges to, and opportunities for, research into local spending.

A municipality’s authority over certain policy areas is often granted by higher levels of government. However, the extent of local governments’ responsibilities often is much broader than what they have decision-making power over. As a result, many distributive activities executed at the local level are not actually decided by local governments. Local government autonomy varies greatly around the world1, so to illustrate some of the common intricacies, I present the situation in Germany.

Authority and Responsibilities of German municipalities

In Germany, municipalities are the lowest of three levels of government, the others being the federal and the state level. Contrary to the federal and state governments, and to popular belief, municipalities do not have a legislative body. Municipal councils, while formed through elections, are entirely part of the executive branch2. Laws concerning the municipal structure and internal organization are given by the respective state.

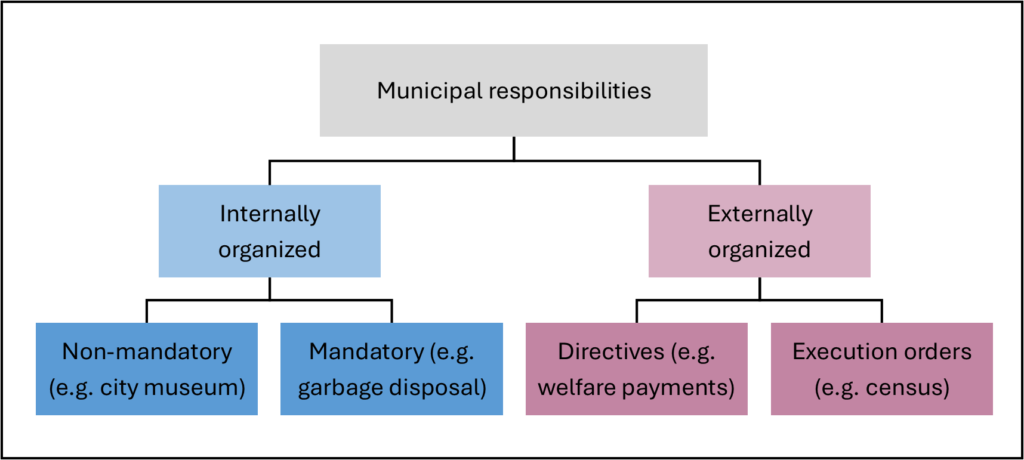

Generally, a municipality’s responsibilities can be separated into multiple groups (Fig. 1). The first group are “internally organized” responsibilities. Regarding these responsibilities, a municipality can decide on the manner of their execution. Some of them are mandatory, meaning a municipality’s implementation needs to fulfill certain requirements set by the state or the federal government. This is the case for the construction of schools or garbage disposal. Non-mandatory responsibilities include things such as public swimming pools or city-funded museums. The local government has full discretion over these and can decide whether these infrastructure items and services are offered and in which capacity.

The second group of responsibilities are the externally organized. They are also carried out by bodies of the local government, but according to directives from the state or federal government. Examples are local elections (standardized by the state) and certain welfare payments (especially SGB II and SGB XII3). The latter are a very important element of every analysis of local budgets. They make up a significant part of a municipality’s consumptive costs, yet the council has very little control over them. The federal government decides the amount and eligibility of these payments for individuals. Yet the payments are made from the municipality’s budget. Moreover, a municipality cannot select its residents and may have a lot of welfare receiving citizens. This turns welfare payments into a huge strain on the budget of many municipalities, especially larger cities. The third group are execution orders. For this, higher levels of government utilize local resources (e.g. employees) for their own processes. Prominent examples are the nationwide census and federal and state elections.

But in the case of Germany, there are even more complications. Even for the internally organized responsibilities, the level of government executing them and making the decisions can be murky. If a municipality is not large enough to fulfill all its responsibilities on its own, it is organized in a county (Landkreis). The county takes over responsibilities that small municipalities cannot shoulder or are better solved on a county wide basis. To what degree these responsibilities are taken over depends heavily on the individual capacities of each municipality. This means that there are many different configurations across the country that are difficult to compare. Larger cities, in contrast, are their own county (Stadtkreis) and take over all responsibilities by themselves. A common example of this is public transport. Big cities maintain their own transportation services, while small towns rely on their county to organize regional public transport.

Income Sources

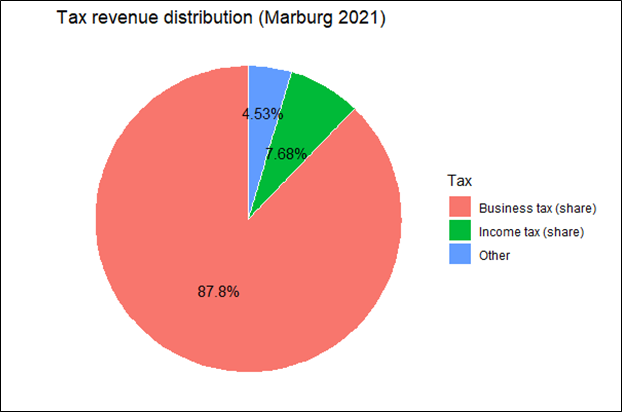

An equally important element of local autonomy are a municipality’s income sources. In Germany, local governments have three main sources of income: Fees and contributions (e.g. parking tickets), grants from higher levels of government, and taxes. Grants from higher levels of government are, by definition, a source of income dependent on other institutions. In addition, they are often bound to a specific project and need to be applied for. The most important income source for municipalities are taxes. There are a few taxes whose proceeds they are entitled to, either fully or partly. Which taxes these are is determined by higher levels of government; municipalities cannot simply impose new taxes when they want to increase their revenue. They receive the full proceeds of the sales tax and the land tax. However, those make up only a small part of a municipality’s tax income. Much more important are the shares they receive from the income tax, especially the business tax. Figure 2 shows the ratio of different taxes of the total revenue in the budget of Marburg in 2021.

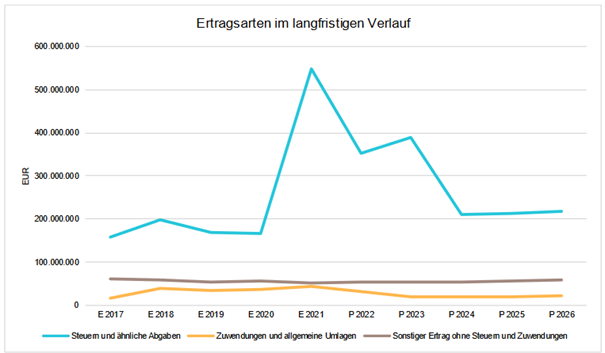

And although Marburg in 2021 is somewhat of an outlier and some of the business tax revenue has to be shared with higher levels of government, the dependence of local governments on the business tax has long been a widely discussed issue. Additionally, municipalities have quite a significant window to determine the business tax rate within their borders. These circumstances can lead to, from the municipalities’ perspective, undesirable outcomes. For example, it leads to a general volatility of municipal income, whose size is in large part determined by local business activity and very cyclical. Additionally, (relatively) large companies play a very important role for the local budget, as their presence and wellbeing can make a significant positive impact on a municipality’s finances. Figure 3 shows the development of Marburg’s income in the past few years and the projection for the next few years. The blue line represents tax revenue. There is a large spike in 2021, almost tripling the budget, due to the establishment of a Covid vaccine plant by BioNTech at the height of the pandemic. Over the following years, Marburg’s income approximates the previous level again.

Obviously, this sudden income spike was very welcome and positive for the city’s financial situation. But on the flipside, the current income structure can lead to dependency on the fortune and goodwill of a few large companies to secure the municipality’s budget size and fund planned projects.[1] If such a company starts struggling or moves to a different municipality, many planned (and promised) projects need to be slashed from the shrinking budget. Some municipalities go to great lengths to avoid this situation, catering to businesses to keep them within their borders (Bischoff & Krabel 2016) or to attract new ones (Becker et al. 2012). This can lead to tax competition between similar municipalities (Buettner 2001; Janeba & Osterloh 2013).

This structure leads to other issues, as well. Municipalities with relatively little economic activity can fall into the trap of both collecting little business tax revenue and having to pay a high amount of social assistance to poor residents. Additionally, the burden of debt reduction can significantly impact a municipality’s allocatable resources.

This predicament is fairly widespread among German municipalities. For example, a coalition of around 70 cities is trying to call for attention to this issue from policymakers on higher levels of government. They argue that they are not able to make necessary investments due to a combination of low economic activity and high debts.

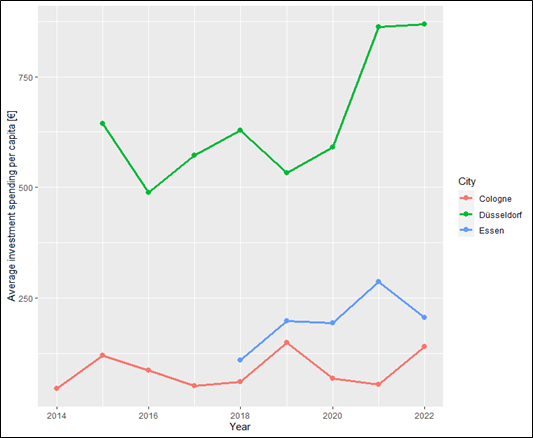

Figure 4 shows investment spending per capita in the years 2014 – 2022 in three German cities: Düsseldorf, Cologne and Essen4.

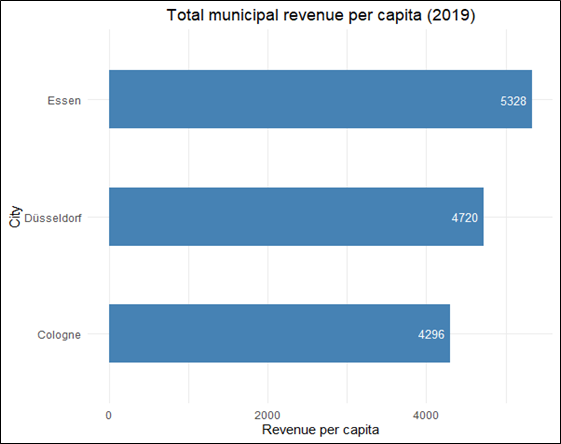

As you can see, each city’s spending varies quite a lot from year to year. Given the mentioned business tax dependency, this is not surprising. Very striking though, is the difference between Düsseldorf and the other two cities. Düsseldorf consistently spends multiple times the amount of the other cities on investment measures. This can have multiple reasons, of course. But looking at the cities’ total revenue per capita in a pre-COVID year (figure 5) suggests that these large differences are not a result of local government income disparities. Rather it implies the inability of Essen and Cologne to allocate their resources to anything but debt reduction, consumptive costs and much smaller investment measures. Both cities are about 3 billion euros in debt each. Düsseldorf on the other hand was debt free until COVID.

Implications for Research

As mentioned above, I wrote this blog entry to raise awareness to some of the challenges involved in analyzing local public spending. So that by engaging with them we can ask more specific and appropriate research questions.

To illustrate, let us stick with our example of local government autonomy in Germany. Recently, we have spoken to councilors from multiple German municipalities. From those interviews we have received the impression that, depending on the financial situation, planned investments for the coming year differ not only in size or amount, but also in kind. On the bright side, it has brought up a multitude of interesting questions that we could go on to test empirically: In times of financial direness, what is the little money for investments spent on? Are these only basic infrastructure projects, or are there still investments into other areas? Are there differences between cities, or do they all act similarly? What kind of projects are the first ones to be pulled out of the hat when the budget for investments increases again?

With our currently running projects, we would like to provide some of those answers. For the moment though, I hope to leave you with some engaging insights into our research.

Footnotes

- For an overview of the autonomy of local governments worldwide, check out the Local Autonomy Index by researchers at the University of Lausanne. ↩︎

- This distinction is made because municipal councils do not have the legislative authority to pass laws. They can only adopt bylaws and regulations, which are subordinate to laws in the hierarchy of norms. Additionally, norm setting is only a small part of a municipal council’s activity, as it is mostly concerned with managing the municipality’s executive responsibilities. ↩︎

- SGB II payments are basic social assistance for individuals who are classified as fit for employment, while SGB XII payments are primarily received by individuals who are classified as unfit for employment due to age or health condition. SGB XII payments are the sole responsibility of municipalities, while costs of SGB II payments are shared with the federal government. ↩︎

- Figure 4 is based on the three cities’ budget reports from multiple years. I have collected and processed the data for my thesis. Some years are missing for Düsseldorf and especially Essen, because the respective budget reports are not publicly accessible. ↩︎

References

Becker, Sascha O., Peter H. Egger, and Valeria Merlo. 2012. “How Low Business Tax Rates Attract MNE Activity: Municipality-Level Evidence from Germany.” Journal of Public Economics 96 (9–10): 698–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.05.006.

Bischoff, Ivo, and Stefan Krabel. 2017. “Local Taxes and Political Influence: Evidence from Locally Dominant Firms in German Municipalities.” International Tax and Public Finance 24 (2): 313–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-016-9419-y.

Buettner, Thiess. 2001. “Local Business Taxation and Competition for Capital: The Choice of the Tax Rate.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 31 (2–3): 215–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-0462(00)00041-7.

Janeba, Eckhard, and Steffen Osterloh. 2013. “Tax and the City — A Theory of Local Tax Competition.” Journal of Public Economics 106 (October): 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.07.004.

Universitätsstadt Marburg. 2023. “Haushalt Und Haushaltssatzung 2023. Band I.” Marburg. https://www.marburg.de/downloads/datei/YTZlNWJhMTZhYWY5N2FhZDUvM3Y2VkNCY0F6SWxOM0plU0xEK1BLTW0zSEtQWm5UVTAxNm9OcmRTSFAxRWpwYW1zT0Fqbkp2eXVwelhUN01UZTVPL0RJL0RkYkxTWXZVOGV1OGpHZWN3ZmFwT3F3MWdmQXdvc005eHE5bEQ5VXNqTStna3dxUDF4dlpDc05r.