As the federal elections in Germany approach, we’re excited to share a series of three blog posts on topics related to the election. All three posts are written by students from one of Eva Wegner’s courses. This post marks the first in the series.

Authors: Hannah Wagner, Cathleen Aretz, George Lalsangliana, and Miriam Novotny

On February 23, 2025, Germany will hold its federal elections, and one party is making headlines: Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). The far-right party has doubled its support since the last federal elections in 2021 and is projected to become the second-largest party in the Bundestag.1 It’s striking that the AfD is also receiving support from groups it openly discriminates against—women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people with migration history.2 What’s more: AfD is the only German party with a Lesbian Spitzenkandidatin. How does this go together? Why do people vote for a party that attacks the basis of their existence and seeks to restrict the rights of minorities?

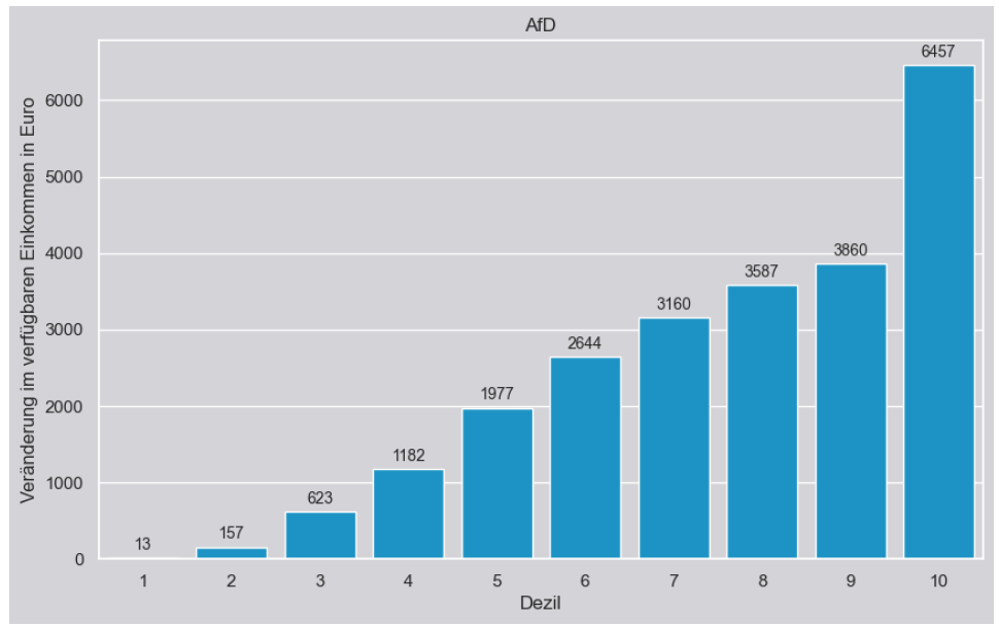

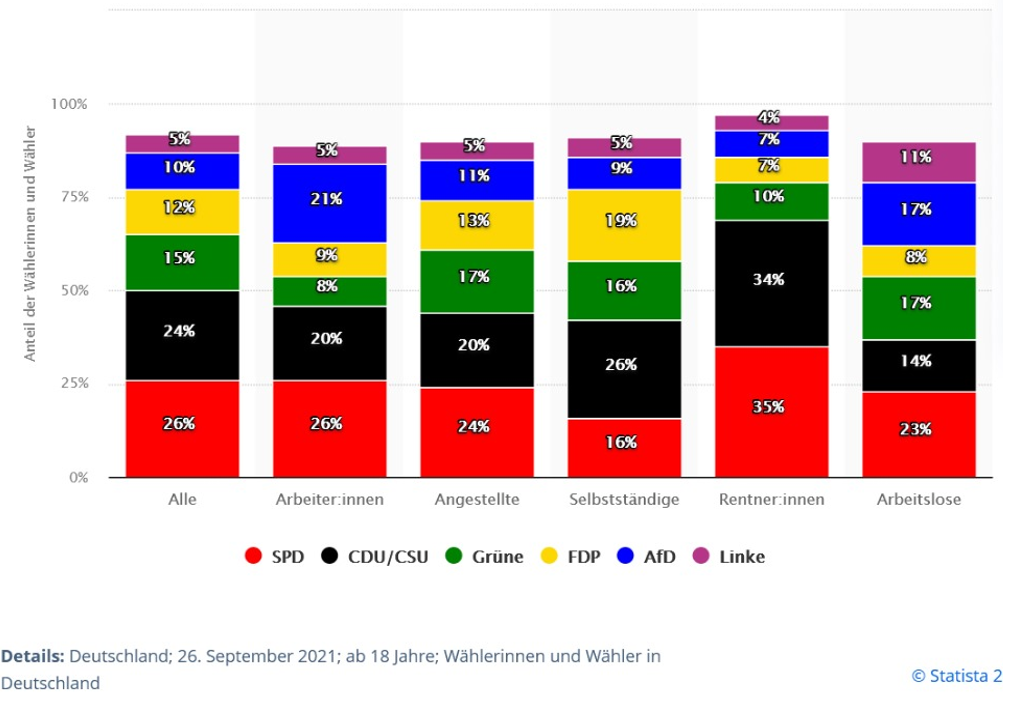

Existence is not only guaranteed by political rights but also needs economic policies that guarantee everyone’s basis of living. Comparisons of the election manifestos show that the AfD’s proposed policies will increase income inequality in Germany and generally benefit richer people more.3 Yet, manual workers are the professional group that supports the far-right the most.4 Quite a high share of people with lower income voted for AfD during the European Parliament elections last year. The results from previous elections show that the impact of socioeconomic characteristics on people’s voting decisions is decreasing. Parties that have existed for a longer time still appeal most to certain socioeconomic groups, but the AfD does not fit into that pattern and appeals to a wide range of professions.5

Unsurprisingly, the AfD does not appeal to most migrant groups. People with a history of migration remain most likely to vote for the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and AfD remains the least popular of the major German parties for them. Yet, for some members of the community, the AfD is increasingly attractive: Compared to other migrant communities, the so-called ‘late-repatriates’ from the former Soviet Union are more supportive of AfD’s policies.6 How does the AfD appeal to these population groups?

“Acting For” the people

As a political party, the AfD represents people. However, representation is more complex and when talking about political representation, there are two main ideas. Descriptive Representation refers to “standing for” the represented based on demographic likeness, meaning a party’s Members of Parliament (MPs) come from the same backgrounds as the people they claim to represent.7 Do they share the same age, gender, ethnicity, or social class?8 And then there is also Substantive Representation – It is “acting in the interest of” the represented, being responsive to their needs and concerns – whether a party actually fights for policies that benefit the people they say they represent.9 Are they creating policies to address the economic concerns of their voters?10 Substantive representation matters because it shows that democracy isn’t only about elections, it is about making sure government actions meet the real needs and dreams of the people. When elected officials truly represent their constituents’ interests, it builds trust, strengthens the democratic system, and leads to policies that effectively tackle the challenges we face every day.

Who does the AfD “Act For?” This is where things get more complicated. The AfD claims to represent “the people” but the AfD frames “the people” as a unified group opposed to elites and migrants, creating an exclusionary identity that marginalizes minority voices, and often prioritizes the interests of high-income people over workers while claiming to be on the worker’s side.11 In their manifesto12, AfD uses the word ‘Volk’ as well as the word ‘Bürger’. Whereas Volk has a more nationalist connotation in German, Bürger refers more neutrally to the citizens of the country. Particularly through the use of Volk, the AfD emphasizes “traditional German identity” rooted in Christianity, which can alienate non-Christian and multicultural communities.13 Yet, Bürger is used much more often than Volk making the manifesto more accessible to a broader public. Despite claiming to represent “workers,” AfD’s planned policies would disproportionately benefit higher-income demographics.14

AfD and Voters – Claims and Beliefs

The AfD claims to stand for “the people” — but who exactly do they mean by that? Do they truly represent the voters they claim to? And most importantly, do the voters they claim to represent actually accept that claim and vote for them?

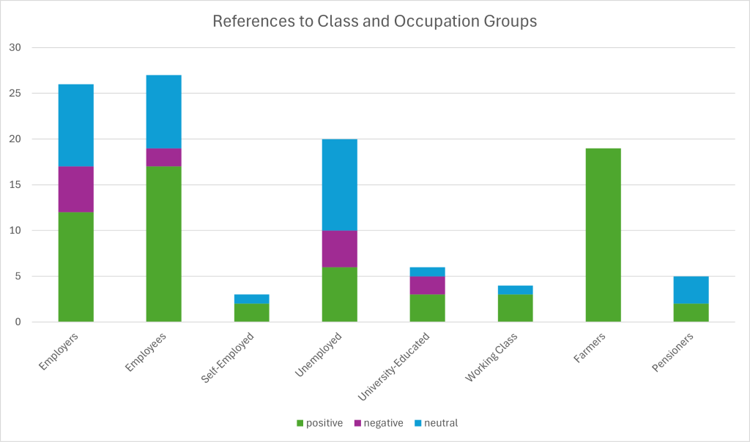

Borrowing from the researchers Reinhard Heinisch and Annika Werner, we’re analyzing the AfD’s 2025 election manifesto to see which classes, genders, and minority groups they frame positively and which negatively. We’re comparing the manifesto to real voting data from Germany’s 2021 election. If the AfD’s message resonated with the groups they claim to champion, we should see strong support from those voters. But maybe also groups they do not mention or mention negatively vote for AfD. Why would they do this?

Being voted into power by the poor, making policy for the rich

AfD claims to be on the workers’ side while often prioritising the interests of high-income people.15 How does this show in the manifesto?

AfD only directly addresses the working class four times in the manifesto for the 2025 Bundestag elections. More general terms (for example taxpayers, skilled workers, public service workers or politicians) that relate to all employees are used much more, but the working class and their economic situation do not take up a lot of space in the manifesto.

Quite surprisingly, unemployed people are mentioned a lot in AfD’s election manifesto. Even though they only make up 6.4% of the working-age population16 the manifesto includes 20 references to this group. This is quite a lot compared to the working class only being mentioned four times. However, how the AfD portrays unemployed people is ambiguous. On the one hand, the party is very critical of the current unemployment benefit system in Germany, but on the other hand, they accuse many welfare recipients of not wanting to work.

But not all welfare recipients are portrayed as lazy. According to the AfD those people who are “really in need” “deserve our support”.17 But who does this include? How can it be the case that some people really need support from the state and others just want to get money for free? And who decides who is really in need? The AfD manifesto leaves open who is lazy and who is “really” in need of support.

There’s one professional group AfD seems to like most: Farmers. Only 1.5% of Germany’s voting population work in agriculture,18 but this group is mentioned 19 times in the manifesto with an incredibly positive framing. Farmers are portrayed as “indispensable” members of the society who “uphold tradition”. On this basis, AfD promises them to reduce bureaucracy, abolish the CO2 tax, and increase their freedom and subsidies.

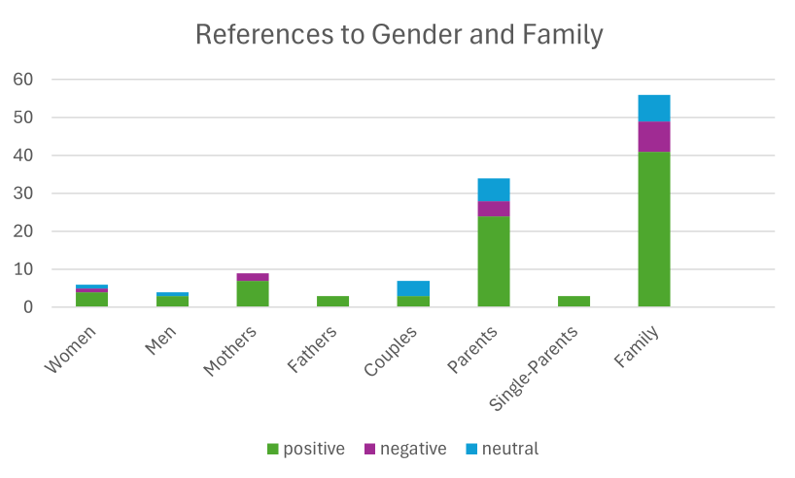

A return to the past to escape the problems of today’s families

Families are a key group in the AfD manifesto. The word ‘family’ is mentioned 56 times with an overwhelmingly positive bias. Families are mentioned more than any other social group. The AfD manifesto stresses their role as the base of society, a safe space for children, an anchor in life, a home, a place of trust, mutual care, safety, support, a space to share joy, find comfort and strength and give and receive love. But AfD also promises concrete improvements to families, particularly financial relief. AfD vows to decrease taxes for families and make it easier for parents to combine family and work. All of these proposed changes should incentivise parents to get more children and allow them to nurse their children at home. Also, there’s a separate paragraph on strengthening families’ autonomy meaning that the state should only interfere in family life in the worst cases as parents know what is best for their children.

Women and men are mainly mentioned in the context of their roles in families. What’s interesting, the term ‘mothers’ is mentioned more often than the term ‘women’, but the term ‘men’ is mentioned once more than ‘fathers’. However, these mentions can be neglected compared to the dominance of the words ‘family’ and ‘parents’. Regarding women’s role in society, AfD emphasises five times that they should not be pressured into abortion. And mothers should be supported if they want to stay at home to care for their children until they are three years old.

Breaking the circle of solidarity

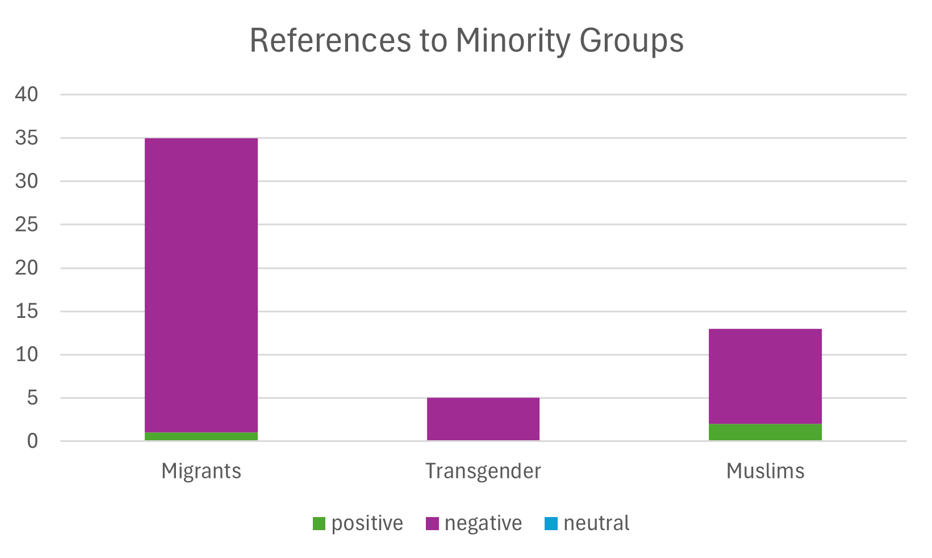

Before discussing if all of these claims work, we need to comment on another group; minorities. AfD has a little bit of identity to offer for everyone. Well, and then there are groups that the party does not exactly like. 14.8% of German citizens have a migration history, 11% of German citizens define themselves as queer19 and 3.5% of German citizens are Muslims.20 The AfD seems to represent these minority groups somehow, while clearly showing racist, anti-queer and anti-Muslim views in its manifesto, as seen in the graph “References to Minority Groups”.

Migrants, which includes foreigners, asylum applicants and refugees, are mentioned 36 times in the manifesto – mostly negatively. The only positive context of migration they are mentioning is when they speak about the “successful integration of thousand immigrants”.21 It remains unclear who this group contains. Maybe the few German resettlers from the former USSR supporting the AfD22 are meant, probably not. Hence, everyone who believes they are themselves well-integrated could believe that they can vote for AfD without having to fear deportation.

Looking at the LGBTQ+ community the most specific group mentioned is Transgender. They are mentioned five times, always with a negative spin. The words Gay, Lesbian, Queer or homosexuals do not appear in the program. Still, these groups might vote for the AfD, because they fear anti-queer sentiment from migrants and are concerned about topics like migration and security.23 A non-representative study showed that only very few queer people would vote for the AfD, and if so, they would be, compared to the voting behavior of other queer individuals, most likely gay men.24 Meanwhile, the AfD acts homophobic like in their law suggestion against same-sex marriage, which was later rejected.25

Muslim people next to Jewish people are the only minority religious group specifically mentioned in the manifesto. 13 times, twice positively, and 10 times negatively. Positive, when Muslims are integrated well, or when in need of support when it comes to the rights of Muslim women. They are mentioned negatively in terms of being open to violence, calling for the Kalifath, and Imams who shall preach in German. The AfD portrays them as anti-queer, dangerous and Islamist. AfD provides a platform for the growing scepticism towards Islam among the German population.26

Jewish people are mentioned two times. However, they are mentioned only in the context of Muslims being hostile against Jewish people and Israel. They exist in the AfD manifesto only as a victim of antisemitic Muslims, weaponizing Jewish people. The fact that the AfD itself holds anti-Semitic positions is made clear by an example in which AfD members were asked to distinguish between quotes by Adolf Hitler and Björn Höcke but were unable to do so.27 Surprisingly, there’s a group of Jewish people who not only identify with the AfD but are also part of it. In 2018, a group of 19 Jewish AfD members even formed the JAfD group.28

Do transgender individuals, Jewish people, and migrantised people now have reason to fear one another, given that they are all targeted, selectively protected, and mostly mentioned in a negative light by the AfD? A confusing circle with food for thought – who should now fear whom?

These groups are clearly played out against each other. Instead of minority groups supporting each other, LBGTQ+ communities are told to fear immigrants and Muslims and people with immigration histories (only the good ones who belong to “the people”) are told to fear gender ideology indoctrination – while all minorities should actually fear the AfD.

Does it work?

So, we established that AfD mentions a lot of different social groups in their 2025 election manifesto. Workers, farmers, welfare recipients and families are highlighted most positively and promised benefits. Do these voter groups actually accept that representation claim and vote for AfD? If yes, why?

The AfD’s appeal is complicated. On the surface, it appears to represent working-class Germans, but its policies suggest otherwise. So why do people still vote for it? One reason is that mainstream parties have failed to address key voter concerns, particularly economic struggles. Many people vote for the AfD not because they fully agree with its platform, but as a protest vote against the political establishment. Years of rapid globalization, industrial restructuring, and regional decline have left them feeling abandoned and ignored by the mainstream parties. For these voters, the AfD represents a way to register a protest vote—a means of voicing frustration over a political system they see as unresponsive.29

In the 2021 federal elections, the AfD received the largest share of votes from manual workers. 21% of workers voted for AfD,30 while in total, AfD only received 10.3% of the votes.31 This is not surprising because far-right parties all over Europe have generally been supported most by people with lower incomes.32 People with less money feel more easily threatened by outside groups who receive support from the state. Migrants who have newly arrived in a country can more easily take over manual jobs than those jobs that require you to speak German fluently.33 AfD seems to be an attractive choice for them even though manual workers are not mentioned a lot in the manifesto.

Unemployed people and welfare recipients are mentioned a lot in the AfD manifesto. Lazy unemployed people are framed negatively, but unemployed people who need support are framed positively. AfD is planning to bring these people to work when in reality the majority of welfare recipients are actually not able to work. Many of them are still children, studying, caring for relatives or even working but don’t earn enough money for their living and therefore receive additional unemployment benefits.34 This ambiguity is a smart move: If I were currently unemployed and receiving benefits, I would probably not think of myself as lazy. Rather, I would think that I deserve the state’s support. I could easily vote for AfD without having to fear that they would force me to end my studies or take a second job next to my badly paid first job. Decreasing the coverage of the social security net would mean that the poverty risk quota in Germany increases by 2.2.35 It is striking that 17% of unemployed people voted for AfD in 2021 even though the planned policies would likely worsen their situation.36

AfD is appealing to unemployed people because it allows them to express their deep discontent with the traditional political establishment.37 Also, unemployed people have personally felt the consequences of economic insecurity and decline, two factors that go together with increased support for populist parties.38 This is particularly pronounced in Eastern Germany which also has a higher unemployment rate.39 Importantly, people who perceive their own personal and financial situation as bad are more likely to vote for populist parties40. They may be drawn to the idea that the country’s political elites have forsaken traditional values and that outsiders are reaping the benefits of a system that has failed ordinary people.41 So the support for the AfD among the unemployed population is multifaceted but closely linked to their experience of how economic decline influenced their personal situation and their lower well-being levels.

With Farmers, the “why” is quite straightforward. Farmers struggle with financial challenges and AfD promises to address these and acknowledge the importance of farmers in society. The strategy seems to work: In 2021, only 8% of farmers voted for the right-wing populists but during the European Parliament election in 2024, 18% did so.42 This clearly shows that farmers increasingly trust AfD to best represent their interests.

Statistics do not tell us if people with a traditional family are more likely to vote for AfD. So we can only evaluate claim acceptance by looking at women’s voting behaviour. Traditionally, right-wing populist parties draw most of their support from male voters.43 But also women increasingly support AfD and as they constitute half of society, reaching this electorate is an important goal for AfD. Whereas only 8% of women voted for AfD in 2021, already 12% voted for AfD in the 2024 European Parliament elections.44

This increase could be due to AfD’s more prominent female leader Alice Weidel as women who lead right-wing populist parties attract female voters. Women are perceived as less radical and therefore the policies they propose are seen as more harmless.45 And when an anti-feminist party is led by a woman, it is more difficult to believe that the party wants to take away women’s rights. Alice Weidel has been co-leading the AfD parliamentary group since 2017 and when she became the co-leader of the party in 2022, she became even more visible in public. In the upcoming federal elections, Alice Weidel is the only female Spitzenkandidatin (top candidate running for the position of Chancellor). This strategy does not only work in Germany: Also the French and Italian right-wing populist parties are led by women and have successfully entered the political mainstream in their countries. These prominent women thus play a strategic role in broadening the voter base of their parties.46 They give the illusion of descriptively representing women without actually substantively furthering policies that strengthen women’s rights.

Reading the AfD manifesto, it becomes obvious that they have a very specific plan for women: Encourage women to stay at home, get many children to solve Germany’s demographic problems without having to rely on migration, and support their husbands who will dominate the public sphere—basically a return to the 1950s if not before that. Generations of feminists have fought struggles to gain more rights for women, make them less dependent on their husbands and increase their say in society. Why do women who benefit from these struggles decide to vote for a party that will likely destroy these achievements? A return to the traditional family model can be attractive for women who are currently doing care work while also working for a salary at the same time. AfD recognises the pressure that this double burden poses on mothers. And, maybe unexpectedly, AfD does not prescribe that it should be the mother who stays at home. Rather, they want either the mother or the father to be able to care for the children without financial fears. Which parents would say no to more kindergarten spaces, higher child benefits and more time with their children?

An alternative for those who are afraid, powerless and feel left behind. While AfD still relies on a mostly white, male voter base, it is successfully expanding its influence attracting people from diverse parts of German society. AfD offers easy solutions for the economic and sociocultural uncertainty many people experience and this has filled a representation gap. For instance, mainstream parties have failed to address issues such as economic concerns47 or grievances prominently. Some people vote for the AfD simply to express their dissatisfaction with the political system, rather than achieving specific policy goals.48 Often this goes hand in hand with accusing other minority groups: Immigrants are accused of exploiting the welfare system, threatening women and LGB persons and taking away the jobs of the unemployed.

Many of these groups increasingly accept these claims. Yet, it is important to stress that minority groups are not the main voter base and target group of AfD. For those who fit into the AfD’s vision of an ideal society—farmers, traditional families, male workers—the party offers rewards. For those who do not—migrants, LGBTQIA+ individuals, progressive women—it offers exclusion.

Many of the people supporting the AfD would likely suffer under its policies. The party’s economic platform favours the wealthy, and its social policies promote division rather than unity. As Germany approaches the 2025 elections, the AfD’s growing appeal raises a critical question: How do we address economic inequality and social dissatisfaction without turning to exclusionary politics? That is the challenge mainstream parties must confront—before it’s too late.

References:

1 “Neueste Wahlumfrage zur Bundestagswahl von Forsa,” Dawum, February 4, 2025, https://dawum.de/Bundestag/Forsa/

2 “Viele unserer schwulen Freunde wählen AfD,” ZDFheute, January 9, 2025, https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/politik/deutschland/bundestagswahl-afd-waehler-gruende-100.html

3 “Reformvorschläge der Parteien zur Bundestagswahl 2025: Finanzielle Auswirkungen,” Leibniz-Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung, January 17, 2025, https://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/gutachten/Bundestagswahlprogramme_ZEW_2025.pdf

4 Geertje Lucassen, Marcel Lubbers, “Who Fears What? Explaining Far-Right-Wing Preference in Europe by Distinguishing Perceived Cultural and Economic Ethnic Threats,” Comparative Political Studies, 45, no.5 (2012): 547-574. doi: 10.1177/0010414011427851

5 Karl-Rudolf Korte, “Sozialstruktur und Milieus: Stammwählerschaft,” Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, July 1, 2021, https://www.bpb.de/themen/politisches-system/wahlen-in-deutschland/335667/sozialstruktur-und-milieus-stammwaehlerschaft/

6 Oliver Pieper, “How immigrant voters could determine the German election,” DW, January, 26, 2025, https://www.dw.com/en/immigrant-voters-germany-2025-election/a-71392397

“Wie wählen Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund?”, Deutsches Zentrum für Integrations- und Migrationsforschung, https://www.dezim-institut.de/aktuelles/wie-waehlen-menschen-mit-migrationshintergrund/

7 Fenichel Pitkin, Hanna. 1967. “The Concept of Representation.” University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520340503

8 Zislin, Luca L. (2022) “Jewish People in the German Far-Right: How AfD is Pandering to Jews to Gain Legitimacy,” Claremont-UC Undergraduate Research Conference on the European Union: Vol. 2022, Article 13. DOI: 10.5642/urceu.RFHV4040

9 Fenichel Pitkin, Hanna. 1967. “The Concept of Representation.” University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520340503

10 Heinisch, Reinhard, and Annika Werner. 2019. “Who Do Populist Radical Right Parties Stand for? Representative Claims, Claim Acceptance and Descriptive Representation in the Austrian FPÖ and German AfD.” Representation 55 (4): 475–92. doi:10.1080/00344893.2019.1635196.

11 Ibid

12 At the time of writing the final version of the manifesto had not been published yet, therefore we used the draft manifesto discussed at the party convention in Riesa, January 11-12, 2025.

13 Heinisch, Reinhard, and Annika Werner. 2019. “Who Do Populist Radical Right Parties Stand for? Representative Claims, Claim Acceptance and Descriptive Representation in the Austrian FPÖ and German AfD.” Representation 55 (4): 475–92. doi:10.1080/00344893.2019.1635196.

14 Ibid

15 Reinhard Heinisch and Annika Werner. 2019. “Who Do Populist Radical Right Parties Stand for? Representative Claims, Claim Acceptance and Descriptive Representation in the Austrian FPÖ and German AfD.” Representation 55 (4): 475–92. doi:10.1080/00344893.2019.1635196.

16 “Arbeitslosenquote Deutschland,” Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt, January 31, 2025, https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Wirtschaft/Konjunkturindikatoren/Arbeitsmarkt/arb210a.html

17 “Leitantrag der Bundesprogrammkommission – Programm der Alternative für Deutschland für die Wahl zum 21. Bundestag,” Alternative für Deutschland, November 28, 2024, https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Leitantrag-Bundestagswahlprogramm-2025.pdf, line 208

18 Arbeitskräfte in Landwirtschaftlichen Betrieben.” 2024. Statistisches Bundesamt. May 3, 2024. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Branchen-Unternehmen/Landwirtschaft-Forstwirtschaft-Fischerei/Landwirtschaftliche-Betriebe/Tabellen/arbeitskraefte-bundeslaender.html?nn=371820

19 Orth, Martin. 2021. “The Varied Republic of Germany.” Deutschland.de. May 17, 2021. https://www.deutschland.de/en/topic/life/diversity-in-germany-facts-and-figures

20 “Islam in Germany: Facts and Figures.” 2023. DIK – Deutsche Islam Konferenz. June 29, 2023. https://www.deutsche-islam-konferenz.de/EN/DatenFakten/daten-fakten_node.html.

21 “Leitantrag der Bundesprogrammkommission – Programm der Alternative für Deutschland für die Wahl zum 21. Bundestag,” Alternative für Deutschland, November 28, 2024, https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Leitantrag-Bundestagswahlprogramm-2025.pdf, line 2060-2061

22 “Wie wählen Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund?”, Deutsches Zentrum für Integrations- und Migrationsforschung, https://www.dezim-institut.de/aktuelles/wie-waehlen-menschen-mit-migrationshintergrund/

23 https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/politik/deutschland/bundestagswahl-afd-waehler-gruende-100.html

24 DISW, Ergebnisse Der LGBTIQ– Wahlstudie 2025: Hohe WählerInnenwanderung in Der Community.” 2025. Echte Vielfalt. 2025. https://echte-vielfalt.de/allgemein/ergebnisse-der-lgbtiq-wahlstudie-2025-hohe-waehlerinnenwanderung-in-der-community/

25 https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/politik/deutschland/bundestagswahl-afd-waehler-gruende-100.html

26 Kortmann, M., Stecker, C., & Weiß, J. (2019). Filling a representation gap? How populist and mainstream parties address Muslim immigration and the role of Islam.

27 https://www.zdf.de/politik/berlin-direkt/afd-abgeordnete-koennen-hoecke-nicht-von-hitler-unterscheiden-100.html

28 Zislin, Luca L. (2022) “Jewish People in the German Far-Right: How AfD is Pandering to Jews to Gain Legitimacy,” Claremont-UC Undergraduate Research Conference on the European Union: Vol. 2022, Article 13. DOI: 10.5642/urceu.RFHV4040

29 WSJ (2025) ‘Meet the Blue-Collar Voters Making Germany’s AfD Mainstream’, The Wall Street Journal, 4 February.

30 ARD. Wahlverhalten bei der Bundestagswahl am 26. September 2021 nach Tätigkeiten (Stimmenanteile der Parteien). Chart 27. September 2021. Statista.

31 “Bundestagswahl 2021: Endgültiges Ergebnis,” Die Bundeswahlleiterin, October, 15, 2021, https://bundeswahlleiterin.de/info/presse/mitteilungen/bundestagswahl-2021/52_21_endgueltiges-ergebnis.html

32 Geertje Lucassen, Marcel Lubbers, “Who Fears What? Explaining Far-Right-Wing Preference in Europe by Distinguishing Perceived Cultural and Economic Ethnic Threats,” Comparative Political Studies, 45, no.5 (2012): 547-574. doi: 10.1177/0010414011427851

33 Michael Bollwerk et al., “Feeling Threatened by Immigrants: The Role of Ideology and Subjective Societal Status,” Ideology, Status and Threat, 2020, https://psyarxiv.com/6dw4y/download?format=pdf

34 Moritz Maier, “Nicht nur Arbeitslose: Daten zeigen, welche Menschen wirklich Bürgergeld beziehen,” Frankfurter Rundschau, July 29, 2024, https://www.fr.de/wirtschaft/empfaenger-sgb-ii-arbeitslosigkeit-arbeitslos-arbeit-deutsche-auslaender-grundsicherung-buergergeld-zr-93205460.html

35 “Reformvorschläge der Parteien zur Bundestagswahl 2025: Finanzielle Auswirkungen,” Leibniz-Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung, January 17, 2025, https://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/gutachten/Bundestagswahlprogramme_ZEW_2025.pdf

36 Marcel Fratzscher, “DIW Berlin: Das AfD-Paradox: Die Hauptleidtragenden Der AfD-Politik Wären Ihre Eigenen Wähler*Innen.,” 2023, https://www.diw.de/de/diw_01.c.879742.de/publikationen/diw_aktuell/2023_0088/das_afd-paradox__die_hauptleidtragenden_der_afd-politik_waeren_ihre_eigenen_waehler_innen.html

37 “Meet the Blue-Collar Voters Making Germany’s AfD Mainstream,” The Wall Street Journal, February 4, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/world/europe/meet-the-blue-collar-voters-making-germanys-afd-mainstream-79350785?reflink=share_mobilewebshare

38 Matthew Polacko, Peter Graefe, Simon Kiss, “Subjective economic insecurity and attitudes toward immigration and feminists among voters on the Right in Canada,” Social Science Quarterly, 105, no.2 (2024): 281-295, https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.13336

Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, Javier Terrero-Dávila, Neil Lee, “Left-behind versus unequal places: interpersonal inequality, economic decline and the rise of populism in the USA and Europe,” Journal of Economic Geography, 23, no.5 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbad005

Amelie Nickel, Eva Groß, “Assessing Regional Variation in Support for the Radical Right-Wing Party ‘Alternative for Germany’ (AfD)—A Novel Application of Institutional Anomie Theory across German Districts,” Social Sciences, 12, no.7 (2023):412, https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12070412

39 Silke Röbenack, “Der lange Weg zur Einheit – Die Entwicklung der Arbeitslosigkeit in Ost- und Westdeutschland,” Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, October 15, 2020, https://www.bpb.de/themen/deutsche-einheit/lange-wege-der-deutschen-einheit/47242/der-lange-weg-zur-einheit-die-entwicklung-der-arbeitslosigkeit-in-ost-und-westdeutschland/#node-content-title-4

40 Adena, M., & Huck, S., 2024. Support for a right-wing populist party and subjective well-being: Experimental and survey evidence from Germany. PLOS ONE, 19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303133

41 Juho Kim. (2018). The radical market-oriented policies of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and support from non-beneficiary groups – discrepancies between the party’s policies and its supporters. Asian Journal of German and European Studies. 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40856-018-0028-7

42 So Haben Die Landwirte Gewählt – Bayerisches Landwirtschaftliches Wochenblatt 39-2021.” 2021. Dlv Digitalmagazin App. 2021. https://www.digitalmagazin.de/marken/blw/hauptheft/2021-39/agrarpolitik/012_so-haben-die-landwirte-gewaehlt

43 Lodders, V., & Weldon, S. (2019). Why Do Women Vote Radical Right? Benevolent Sexism, Representation and Inclusion in Four Countries. Representation, 55(4), 457–474. https://doi-org.chain.kent.ac.uk/10.1080/00344893.2019.1652202

44 “Wer Wählte Was?” 2021. Tagesschau.de. 2021. https://www.tagesschau.de/wahl/archiv/2021-09-26-BT-DE/umfrage-werwas.shtml.

45 Franzi von Kempis. 2024. “Warum Wählen Frauen Die AfD?” Substack.com. Adé AfD. September 9, 2024. https://franzivonkempis.substack.com/p/warum-wahlen-frauen-die-afd.

46 Wineinger, C., & Nugent, M. K. (2020). Framing Identity Politics: Right-Wing Women as Strategic Party Actors in the UK and US. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 41(1), 91–118.

47 Heinisch, Reinhard, and Annika Werner. 2019. “Who Do Populist Radical Right Parties Stand for? Representative Claims, Claim Acceptance and Descriptive Representation in the Austrian FPÖ and German AfD.” Representation 55 (4): 475–92. doi:10.1080/00344893.2019.1635196.

48 Plescia, C., Kritzinger, S., & De Sio, L. (2019). Filling the Void? Political Responsiveness of Populist Parties.